JFK called it ‘Cuber’. This small island, just 90 miles off the coast of Florida, became ours after the Spanish-American war. It has preoccupied American presidents for the last 60 years, and it still isn’t out of our hair.

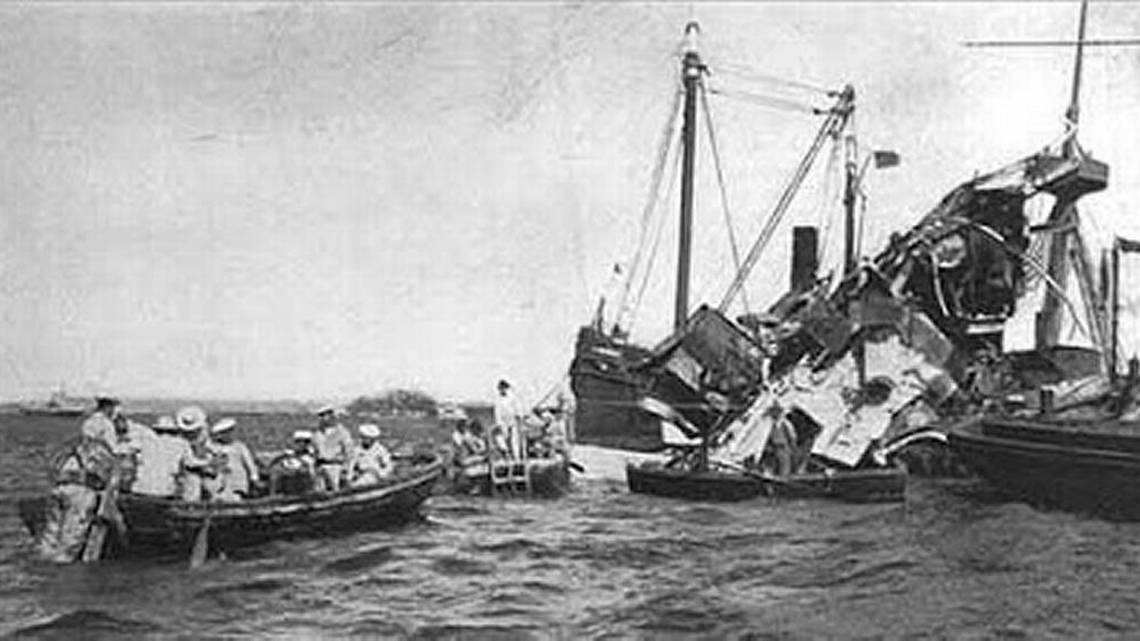

Cuba catapulted into American headlines on the night of February 15, 1898, when the Battleship Maine blew up at anchor in Havana harbor. 266 of the 350 men aboard were killed. Journalists and politicians immediately blamed Spanish operatives. Later investigations suggested that the explosion was most likely accidental – probably caused by a coal bunker fire. But the resulting public hysteria sent us to war against Spain.

“Spain, Spain, you oughta be ashamed, for blowing up our Maine,” my Grandma used to sing, long after the event. We dashed off to war with the “Remember the Maine!” echoing across the country. Some commentators said the American public was “hungry” for a war, as 33 years had now elapsed since the Civil War. (Admirable motivation.)

“O dewy was the morning, upon the first of May. And Dewey was the admiral, out in Manila Bay…” By summer’s end, 1898, Admiral Dewey had sunk the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay, Teddy Roosevelt had charged up San Juan Hill, and Spain had ceded Cuba, along with the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam, to the USA. ‘Cuber’ was ours – the start of a century of turmoil all out of proportion to the island’s size. But its geological location in the Caribbean, just 90 miles from Florida, did make it strategically important.

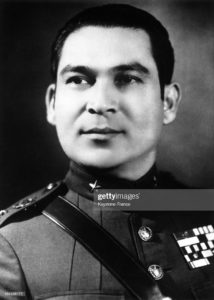

Appointed governors and elected presidents ruled Cuba until 1933, when Fulgencio Batista Zaldívar, a sergeant in the Cuban Army, seized the government in what became known as the “Revolt of the Sergeants.” Batista forced President Ramón Grau San Martín to resign in January 1934. For the next decade, Batista ran the country from deep background.

American business had feared President Grau’s liberal social and economic revolution, so they welcomed Batista and saw him as a stabilizing force who respected their interests. During this time period Batista formed a friendship and business relationship with Mafia Don Meyer Lansky that lasted over three decades.

Batista enjoyed the support of President Franklin Roosevelt because he was friendly to the USA and permitted American business to flourish. He was elected president in 1940, but in 1944, Grau San Martín was again elected, and Batista relinquished control. Subsequently he lived luxuriously in Daytona Beach, Florida, until 1952, when he again seized the government of Cuba – this time overthrowing elected President Carlos Prío Socorras three months before elections that Batista would certainly have lost. Also running in that election (for a different office) was a young lawyer named Fidel Castro. In March 1952, Batista’s government was formally recognized by President Truman.

Batista now wielded absolute control, and many soon began to fear his power. One of these was Fidel Castro, who began his campaign against Batista by attacking the Moncada Army Barracks in Santiago in July 1953. Batista ruthlessly defeated the incursion and ordered ten rebels executed for every Cuban soldier who had been killed. (Fifty-nine rebels were actually executed.)

With most rebels, including Castro, in jail or dead, Batista initiated his gangster-partnership regime. The Mafia built casinos and hotels, and Lansky made Cuba into an international drug haven. It was said that the bagman for Batista’s wife collected 10-30% of the casino profits each night, in cash. Even minor officials became rich after just a few years of government service.

The situation in Cuba finally attracted the attention and concern of the United States government. Unrest also surfaced among the Cuban people, who began to call for legitimate elections. But Batista consolidated his power and refused any concessions. He was so confident that he released Castro and survivors of the Moncada attack in May 1955, hoping to appease his critics. To avoid possible assassination by Batista’s military police, Castro went to Mexico to plan his revolution.

Batista continued to rule Cuba with an iron fist, ruthlessly suppressing all protests and demonstrations. Several opposition leaders were killed, and the University of Havana was closed in 1956 because of student unrest. (It reopened in 1959, after Castro’s revolutionary victory.)

The Castro brothers and Che Guevara returned to Cuba in December 1956. This marked the start of the armed conflict which ultimately led to Batista’s overthrow and flight to the Dominican Republic on January 1, 1959. (Batista died in Portugal on August 6, 1973.)

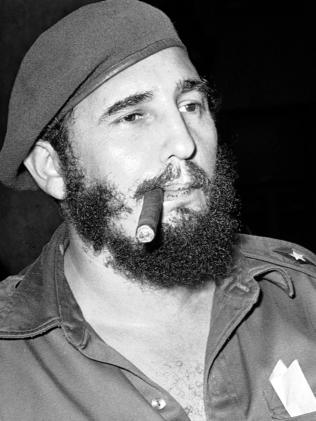

As a newsboy in 1959, I read the news each day as I walked my route. When Castro drove Batista into exile and took over Cuba, the 33-year-old was hailed as a romantic figure in the mold of the Spanish Civil War rebels. Ernest Hemingway and others who had covered that war as young journalists were still around, and the papers were filled with admiring human interest stories of the dashing young revolutionary who had unseated the mobbed-up Batista and his henchmen. It was1936 and For Whom the Bell Tolls1 all over again.

I can still recall how the tone changed to concern as the daily count of executions mounted into the hundreds and then thousands. Reports also emerged of Castro’s possible communist affiliation. Soon it was definitely established that Castro was a communist. It was suspected (but not confirmed) that the Soviets had backed his revolution. This was while the American public still naively thought that a successful armed revolution, with real guns and bullets, could be mounted on a romantic shoestring.

Overnight, Castro changed from a Cuban George Washington to a villain who had betrayed us by being a commie. The American public was outraged, and the Eisenhower administration – not to mention the CIA – was embarrassed that communists had been allowed to take over a country just 90 miles from our shores. It was this outrage and embarrassment that essentially formed the basis for American policy toward Cuba for the next 50+ years.

By the time of John Kennedy’s inauguration, plans had been laid for an invasion of Cuba by expatriate armed forces. President Kennedy approved the plans and initially backed American support. But when the invasion force of 1,400 CIA-backed exiles actually hit the beach at the Bay of Pigs, on April 17, 1961, the president withheld crucial American air support, causing the invasion to fail. 114 soldiers of the invasion brigade were killed; 1,189 became prisoners. President Kennedy publicly confirmed American involvement and took the heat for the failure.

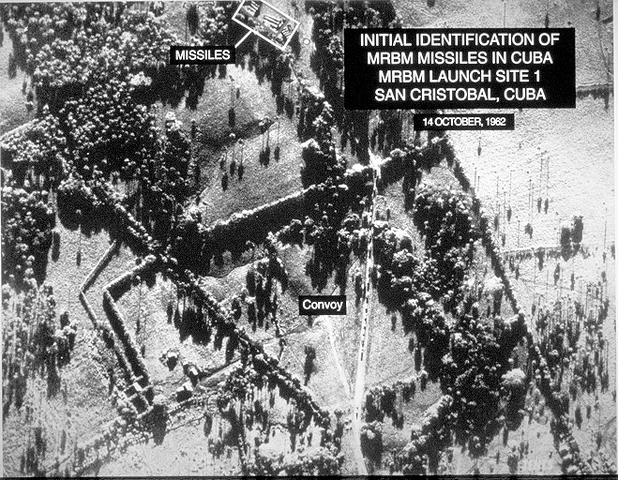

Soviet support of Castro developed into a full blown nuclear crisis in 1962, when aerial reconnaissance photos revealed construction of ICBM sites in Cuba. Mr. Kennedy’s military advisors indicated that these missiles – if armed with nuclear warheads – would constitute a grave threat to numerous American cities. An intense 10-day staring match ensued between the USA and the Soviet Union to see who would blink.

My wife and I were newlyweds in October 1962 when we sat near the radio listening to Mr. Kennedy announce that he had placed a military embargo on Cuba. All inbound ships would be stopped and boarded on the high seas to determine if they contained contraband of war – particularly parts and weapons for ICBM sites. Any such cargoes would be seized. ‘This is it,’ thought many for whom Korea and WWII were still fresh memories. We were certain it meant war with the Russkies.

After a tense period, during which some Russian ships turned back, Russia announced that they would dismantle the missile sites. Only years later did we learn that this decision was probably facilitated by JFK’s secret deal with the USSR which included removal of our missile sites in Turkey. But in ’62 the nation heaved a great sigh of relief, and ordinary folks like us went back to work and school with the cloud of war removed.

During Mr. Kennedy’s administration various plots (e.g., MONGOOSE and ZR/RIFLE) were hatched to assassinate Fidel Castro. Cuban exiles and Mafia figures, including Sam Giancana, John Rosselli, and Santos Trafficante, were complicit in these, as they were financially motivated to restore Cuba to its status quo ante. Attorney General Robert Kennedy was aware of the conspiracies and encouraged them without explicitly involving American assets.

Ultimately, it was President Kennedy who was assassinated in November 1963. Author Debra Conway believes that “…the conspirators used the Castro plots for ‘window dressing’ for the true plot to assassinate President Kennedy. [The Castro plots] may not have been true attempts to kill Castro at all, but a way to implicate others.”2

The 1988 British TV production, The Men Who Killed Kennedy3, presented the premise that three Corsican assassins were imported through Mexico and into Texas to engineer JFK’s murder in Dallas. And in 1991 Oliver Stone’s film, JFK, presented the theory that the president’s murder was planned and carried out by agents of the CIA.

Whatever the facts, Castro survived, Mr. Kennedy was dead, and our Cuban policy was in shambles. Miss Conway further writes2:

“Attorney General Robert Kennedy … we now know played a major role in rendering inaccessible much evidence in the case of his brother’s murder. The deep remorse shown by RFK and his actions afterwards are only explainable when we allow that he believed – or was led to believe – he was somehow responsible for his brother’s death through his continued encouragement …of the Cuban exiles and their actions against Castro.”

As the decades marched onward toward the end of the century, America’s attitude toward Castro remained guardedly hostile, but not overtly so. No more assassination plots were countenanced by CIA or DoJ officials. Instead, various embargoes were placed on Cuba which made it nearly impossible to obtain automobile parts and similar everyday items. Once the jewel of the Caribbean, Cuba slowly slipped into shabby third-world status.

American asylum was usually granted to any Cuban refugee under a general policy that encouraged emigration from Cuba. The Clinton Administration made a notable exception to this policy when six-year-old Elian Gonzalez was found floating in the sea off Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, late in 1999. His mother, step-father, and six other passengers had drowned in their attempt to reach the USA from Cuba. Although a judge granted Elian asylum, administration officials seemed determined to curry favor with Castro by returning the boy to Cuba.

A months-long legal battle ensued, culminating in the armed seizure of the boy by what the media called “storm troopers” (see photo), from the home of relatives in April 2000. He was remanded to the custody of his natural father, who then returned him to Cuba. The incident became a cause célèbre in the 2000 election, and is credited by some analysts as having lost Florida for Mr. Gore, who had supported Elian’s return to Cuba.

In 2004 the Bush administration instituted new measures intended to stem the flow of hard currency to Cuba and hasten the end of Fidel Castro’s rule. Cuban-Americans were prohibited from visiting relatives in Cuba more than once in three years. The amounts of American currency they could spend and give to relatives was reduced. The White House also intensified propaganda broadcasts and increased financial support to anti-Castro groups in Cuba.4

I’m not astonished by very much anymore, but Mr. Bush’s actions astonished me. Castro was 78 years old. His country was a dump, and the Russians had deserted him long ago. He was hanging on by a thread, and wasn’t remotely a threat to us or anyone else. Yet we were still trying to bring him down. Why were we doing this?

We had been fixated on this small island for a half-century. We let the gangster-pol Batista turn Cuba into a Caribbean Las Vegas while we buffed our nails. We cheered when Castro threw Batista out; then booed and hissed when our hero turned out to be a commie. Our ill planned invasion attempt got stuffed. We tried to whack Castro, but our guy got whacked instead. Then we tried to starve him out. Finally, we were keeping him from getting any dollars. After 45 years, we were still spending money and valuable presidential time trying to unseat an old man who had proved tougher than a brass walnut. Good grief!

We have illiterate high school graduates. Teens don’t know when the Civil War happened (or what it was about). Housewives think George Bush invented big government. Grownups believe presidents create jobs. Instead of working, Ignorant young fools are wandering around shopping-malls with their butt-cracks showing. But our government was still trying to knock Castro over.

I’m starting to sound like that guy in the film Network who leans out the window and yells, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not gonna take it anymore!”

I didn’t agree with much that Barack Obama did as president, but I have to admit that his attempt to normalize relations with Cuba and help the country get back on its feet was a step in the right direction – even if Fidel’s superannuated brother Raúl was still governing by their witless socialist policies. This obsession had to end. Our Get Castro Department needed to close up shop, and I hope it did.

But now, at this writing, Cuba is in the news again. A Biden Administration official says Cuban refugees arriving by sea will be turned back. Why? Because it’s too dangerous? Nope. Commentators say Democrats don’t want Cubans coming in because they’re wise to the “crock” of Communism and will probably vote Republican if they become citizens.

Meanwhile, Mr. Biden is letting hundreds of thousands of illegals stream across the Tex-Mex border because his party thinks they’ll become dependable Democrat-voters. Is this where we are now? (Hello! Is anyone in there?)

OK. We couldn’t beat Castro. He was too tough or too smart; or our team was incompetent. He embarrassed us. Whatever. So we’ve kicked Cuba and its people around for 60 years.

Our history with Fidel’s Cuba reminds me of something I heard an old veteran say about military leadership during the last years of World War I:

“Finally, there was no thinking going on by anybody, anywhere.”

Enough!

**********

- Hemingway’s great novel of the Spanish Civil War.

- Castro Assassination Plots; Debra Conway. http://www.jfklancer.com/cuba/castroplots.html

- The Men Who Killed Kennedy – https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=The+Men+Who+Killed+Kennedy+Episodes&FORM=VDMHRS

- “Bush Steps Strengthen Castro Regime,” Paolo Spandoni; Washington Times; July 5, 2004