While walking my paper-route in the fall of 1957, I read about the drama playing out at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Following the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education case – in which the Supreme Court ruled that state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students were unconstitutional – the Little Rock public schools had finally moved to integrate its high school by enrolling nine black students.

Those students – later called “The Little Rock Nine” – were met by an angry crowd of white demonstrators who blocked entrances to the school. Subsequently, Governor Orville Faubus – an outspoken opponent of the Court’s desegregation ruling – ordered the Arkansas National Guard to Little Rock to prevent the black students from entering the school.

Governor Faubus’s action prompted civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., to telegraph President Eisenhower, urging him to “…take a strong, forthright stand in the Little Rock situation.” Dr. King said that a failure to oppose the injustice of the governor’s action would set the process of integration “back fifty years,” adding, “This is a great opportunity for you and the federal government to back up the longings and aspirations of millions of people of good will, and make law and order a reality.”

Following Dr. King’s missive, the president sent a contingent of the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to restore order and enable the minority students’ entry into the school. Gradually, the protests melted away, and the nine students were allowed to attend classes without significant incident. In the spring of 1958, Ernest Green became the first black student to graduate from Central High School.

These incidents helped our country turn a corner in the long campaign to afford black citizens full participation in the nation’s education, commerce and governance. Although the change was difficult for people who had lived in segregated communities all their lives – both above and below the Mason-Dixon Line – reasonable people could see the absurdity of wasting the great reservoir of human potential represented by people who had been denied entre to main-stream American society for generations because of their skin-color. It simply made no sense. Professional and college sports had already recognized this by the time of the Little Rock integration. Black baseball, football and basketball players had become great stars, widely applauded for their skills – even by white fans. It was long past time for the rest of the country’s institutions – particularly public education – to follow their example.

Although it is not much mentioned nowadays, President Eisenhower’s decisive action against the unlawful mobs in Little Rock established an important model for future administrations to deal with racial unrest situations. That model is not always followed, but when it is, the results are generally salutary.

Just five years after Little Rock, in the fall of 1962, a black Air Force veteran named James Meredith was met by angry demonstrations – riots, really – when he tried to enroll at the University of Mississippi (“Ole Miss”) in Oxford. This was a delicate political matter for President Kennedy, as Mississippi was then a solidly Democratic state which had cast its electoral votes for him in 1960. In private discussions, Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett had promised Mr. Kennedy that he would protect James Meredith. Later, however, he reneged and publicly vowed to keep Ole Miss completely white.

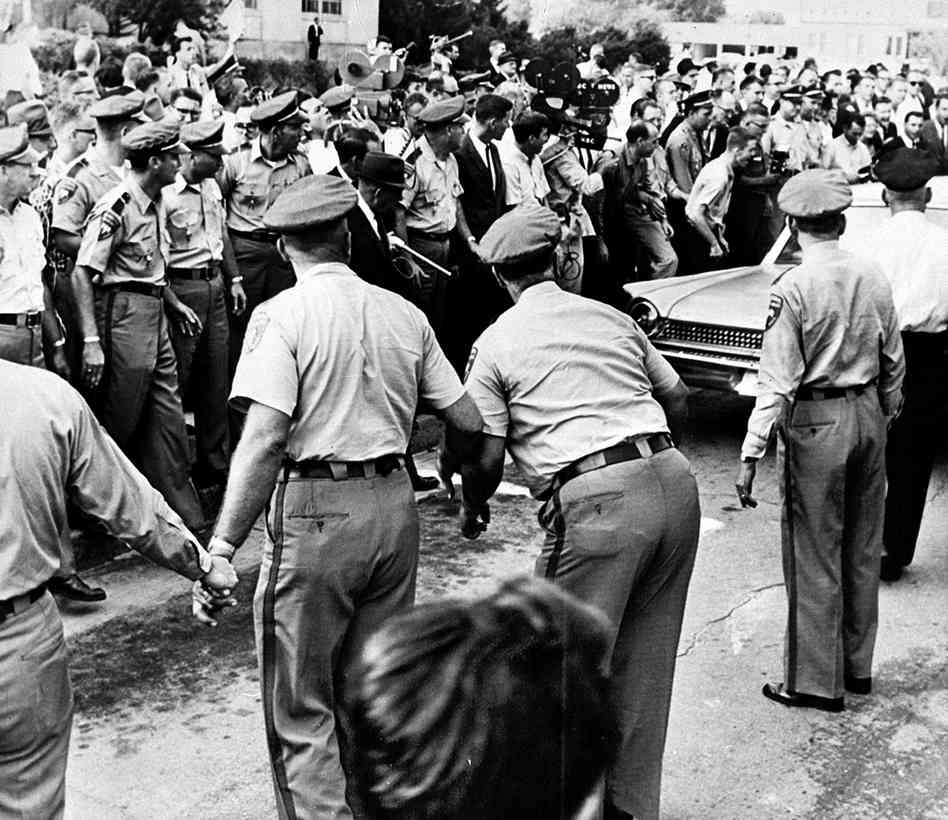

With this encouragement from Governor Barnett, violence erupted on the Oxford campus when Mr. Meredith tried to enroll and attend classes. In response, Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent 500 US Marshals to Oxford to restore order. In the first night of rioting, two civilians were killed – one a French journalist – and nearly 70 people were wounded. Mississippi Highway Patrolmen were replaced by the marshals, who were reinforced by military police from the Army’s 503rd Military Police Battalion. The latter were ordered to the campus by President Kennedy. Also assisting federal units at the university were: several thousand troops from the 2nd Infantry Division; agents of the U.S. Border Patrol; federalized units from the Mississippi National Guard; and U.S. Navy medical personnel.

When Major General Charles Billingslea, commander of the 2nd Division, entered the gates of the university, his car was firebombed. The general and his aides – amazingly unhurt in the burning car – were able to force open the door and crawl to safety under fire. General Billingslea ordered his troops not to return fire, thus de-escalating the situation and preventing much potential injury. Mr. Kennedy’s strong, decisive action had kept a volatile situation from spinning completely out of control.

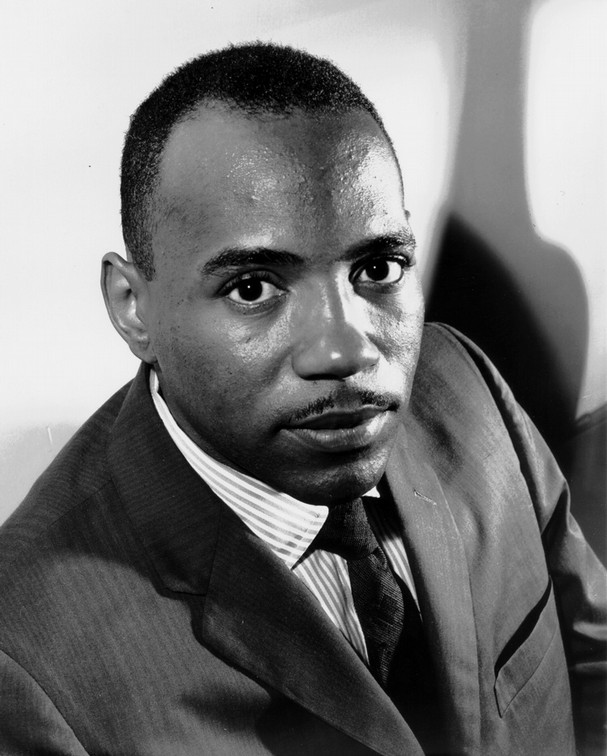

James Meredith attended classes without incident through the ensuing academic year, graduating with a political science degree in the spring of 1963. In 1966 he was shot and wounded during his “March against Fear” – a walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, intended to promote black voter-registration. After he was injured, others completed the march for him. Now 86, he still lives in his birthplace of Kosciusko, Mississippi, after a long and distinguished career in civil rights activism.

I relate these important incidents in our history to show that racial unrest is not a new problem, and to note that good presidential examples have been set for handling such situations. The core of these examples, however, is not talk. It is action that demonstrates a commitment to restoring order, while countenancing absolutely no violence.

In August 2014, the fatal shooting of an unarmed black teen-ager by a white policeman in Ferguson, Missouri, sparked nearly two weeks of protests, looting and street-violence. Exactly how the shooting transpired remains unclear, but evidence eventually showed that the victim, Michael Brown, 18, had committed a strong-arm robbery of a convenience store just moments before he was stopped by Patrolman Darren Wilson. Accounts vary of why Officer Wilson opened fire. There were indications – not widely published – that Brown had injured Officer Wilson and attempted to seize his weapon. Various racial agitators attempted to suppress the store’s surveillance video, which showed Michael Brown accosting the owner as he stole a box of cigars.

Local police were deployed in military-style riot gear when the protests began, but this gesture did not control the unrest. Governor Jay Nixon then recalled all local police and dispatched Missouri Highway-patrolmen, commanded by Captain Ron Johnson, to take over enforcement duties. Initially, Captain Johnson’s unit seemed to have calmed the situation, but later nights erupted in widespread looting which the state police did little to stop.

From his vacation digs on Martha’s Vineyard, President Obama “deplored” the violence in Ferguson and pleaded for calm, while signaling sympathy with protestors’ anger over Brown’s death. Finally, on August 20, Mr. Obama took decisive action. No, he didn’t send the 101st Airborne. By jingo, he got really tough – he sent a lawyer. Attorney General Eric Holder was dispatched to Missouri to oversee the indictment and prosecution of Officer Wilson. I saw a news-clip of Mr. Holder greeting Captain Johnson with the words, “You d’man” – evidently meant to convey racial solidarity with that black officer and other black citizens.

Why Mr. Obama did not send troops to Ferguson is unclear, but politics was probably the reason. Those people marching, yelling and looting were constituents who had elected Mr. Obama to “transform” the country. Sending troops would have offended them, just as the troops JFK sent to Oxford, Mississippi, probably offended the people rioting against James Meredith. Despite the political calculus, JFK knew he had to send a clear signal against lawlessness and violence to the citizens of Mississippi, as well as to the entire country.

But Mr. Obama did not send that signal. Indeed, it was not clear if he understood that it should be sent – that it must be sent! Restoration of quiet and order was essential in Ferguson. Nothing productive could be accomplished with agitators, looters and hustlers roiling the waters and endangering the public. People needed to return to their homes and let justice take its course. Mr. Holder’s arrival didn’t calm things down, and the contribution his presence made to “justice” was unclear.

Despite Mr. Holder’s “oversight,” Officer Wilson was ultimately vindicated when a grand jury declined to indict him for the shooting. An independent Department of Justice investigation also concluded that no clear evidence contradicted Wilson’s account that Brown had attacked him and was attempting to grab his weapon. Photos showed that Wilson had bruises on his face after the incident.

The DoJ investigation also found that the “Hands up, don’t shoot” story – which gained national currency after witnesses said Brown was trying to surrender when he was shot – was inaccurate. “There is no evidence upon which prosecutors can rely to disprove Wilson’s stated subjective belief that he feared for his safety,” the Justice Department’s report said.

Rioters and race-hustlers across the country were sure Officer Wilson had committed a crime, but the evidence did not support that claim. That’s why we employ due process, instead of just letting a mob take over. I am sorry for the family of Michael Brown. His life will never be lived out to what it might have been, and his family will no longer have his presence. It is a wretched business. I cannot imagine the pain of it.

Evidence that came to light later indicated that Brown’s own actions might have led to his death. Brown was a hulking young man, evidently accustomed to throwing his weight around, as the store-video shows. In the wake of that robbery he might have acted belligerently toward Officer Wilson. Brown also had two companions. A single, unarmed officer would have been no match for three strong young men. Did Officer Wilson panic? We don’t know. But his life will be forever changed. This tragic event will always haunt him. How we all wish things had turned out differently.

In the tech-business world, where I spent my own career, we always looked for lessons-learned and useful recommendations whenever something untoward happened. We should do that with reference to Michael Brown’s death, too. Accountability has a certain value – not to be neglected – but we need more than that from such incidents. If we can’t learn anything, these terrible things will keep happening over and over.

My main recommendation would be for police always to travel in pairs, as they once routinely did. Why is this no longer so? Is it a question of money? If so, we need to find the money. Police-teams should be trained and equipped to restrain unruly individuals without resorting to deadly force, except in the most extreme situations dealing with an armed adversary. The partners would back each other up to ensure that no individual threatened physical harm. In the Michael Brown incident, the presence of a partner supporting Officer Wilson could have allowed everyone to walk away without any shooting. At the very least, Officer Wilson would have had a reliable witness to support his account of events.

Ferguson, Missouri – 2014

We have to do better. I believe we can, but we have to want to enough to make changes. And as Ike and JFK showed, it’s important for a president to lead. When you’re the Big Guy, you don’t get to hang back to avoid political complications.