The national hubbub over the televised “debate” between vice-presidential candidates – J.D. Vance (U. S. Senator from Ohio) and Tim Walz (Governor of Minnesota) – has produced a good opportunity to review how important past vice-presidents have sometimes been, as background for considering how important they might be now. Accordingly, I’ll sketch some vice-presidential history in the following paragraphs.

EARLY YEARS

In presenting this abbreviated history of the early vice-presidents I hope to demonstrate how important the office often was – or suddenly became – during our republic’s formative years. With a few exceptions, the early vice-presidents aren’t figures familiar to most Americans (although some of us are old enough to have known some of them personally). As my readers will see, many of those guys were exceptional characters who helped form the new nation, but not without some degree of disruption. The contention they sometimes generated should also be instructive – particularly in our present circumstances.

John Adams (1789 to 1797). Mr. Adams was George Washington’s VP, so he assumed some modeling responsibilities as the first holder of the office. For the most part he kept a low profile while presiding over the Senate, as prescribed by the Constitution. By all accounts he was a very smart and accomplished man, but he was nothing like George Washington – either in style or stature. Nevertheless, when GW stepped down after serving two terms, Mr. Adams stepped up to stand for the presidency in 1796 as the Federalist candidate. He was opposed by Thomas Jefferson on the Republican-Democrat ticket. There were no vice-presidential candidates in that election, so under the rules at that time, the presidential candidate who came in second – i.e., Mr. Jefferson – became the vice-president. It was the first (and only) time that the president and vice-president belonged to different parties.

Thomas Jefferson (1797 to 1801). Mr. Jefferson kept the same low profile as John Adams during his VP term, but he was also preparing to stand for the presidency again in 1800. In that election the custom of the second-place candidate becoming the vice-president was no longer operative. So Mr. Adams had his own Federalist VP candidate, Charles Pinckney – a veteran of the Revolutionary War – while Mr. Aaron Burr was Mr. Jefferson’s VP candidate on the Democratic-Republican ticket. Under the pre-1804 rules, each member of the Electoral College had two votes to cast. A long and bitter campaign, in which each party predicted the “end of the republic” if the other party won (sound familiar?), finally ended with Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr both winning 73 electoral votes. Mr. Adams won 65 votes, and Mr. Pinckney won 64. This meant that the Democratic-Republican ticket would take both the presidency and vice-presidency, but the Constitution specified that the House of Representatives should choose between Jefferson and Burr because their electoral vote-totals were identical. Mr. Burr was criticized for campaigning against Mr. Jefferson for the presidency before the contingent election – somewhat gauche, since he and Jefferson’s were in the same party. Each state delegation cast one vote, and a candidate became president by winning a majority of the state delegations. Neither Burr nor Jefferson could win on the first 35 ballots of the contingent election. Most Federalist representatives backed Burr, and all Democratic-Republican representatives backed Jefferson. But Alexander Hamilton, a Federalist, disliked Burr, so he convinced several Federalists to switch their support to Jefferson. This gave Jefferson the win on the 36th ballot. Jefferson thus became the second incumbent vice president to be elected president. But the well had been poisoned.

Aaron Burr (1801 to 1805). Mr. Burr served as vice president during Mr. Jefferson’s first term, although he clearly wasn’t very happy about listening to boring speeches in the Senate and playing second fiddle. He and Mr. Jefferson were frequently at odds, personally and politically, so the president kept him on the sidelines and didn’t choose him for vice-president in his second term. The grudge Burr carried against Alexander Hamilton for having denied him the presidency in the 1800 election finally led him to challenge Mr. Hamilton to a duel. They fought it with pistols in July 1804. Mr. Hamilton was mortally wounded and died on the field. Although dueling was illegal, Burr was not prosecuted. But this disastrous event ended his political career. Thomas Jefferson’s presidency led to the rise of the slavery-aligned states’ rights Democratic Party. The Federalists never elected another president after Mr. Adams.

George Clinton (1805 to 1812). Born in 1739, Mr. Clinton served as a lieutenant in the colonial militia during in the French and Indian War. After the war he began practicing law and served as a district attorney for New York City. He then became Governor of New York in 1777, serving until 1795 – the state’s longest-serving governor. Mr. Clinton supported independence during the Revolution and served in the Continental Army, despite his gubernatorial position. After the war he opposed adoption of the U. S. Constitution because it lacked a bill of personal rights. That opposition boosted him into leadership in the newly formed Democratic-Republican party during the early 1790s. He contended for the vice-presidency in the 1792 election but was defeated by John Adams. In the 1804 election he replaced Aaron Burr as Mr. Jefferson’s vice-president, and in the 1808 election he also became James Madison’s VP – serving until his death in April 1812. Thus, he was the first vice-president to serve under two presidents, and the first VP to die in office. The office remained unfilled for the balance of Mr. Madison’s first term.

Elbridge Gerry (1813-1814). Born into a wealthy merchant family in 1744, Mr. Gerry opposed British colonial policy in the 1760s and was active in early stages of organizing resistance in the revolution. Elected to the Second Continental Congress, Mr. Gerry signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation, but he and two other attendees of the 1787 Constitutional Convention refused to sign the drafted Constitution because it did not include a bill of personal rights. After its ratification, he was elected to the inaugural Congress where he was a vocal advocate of individual and state liberties. In that role he actively participated in drafting and passing the set of Constitutional Amendments that became our Bill of Rights, While in Congress he became known for the political practice of “gerrymandering,” which is named after him. He became vice-president in 1813 for James Madison’s second term, but he served only 20 months. His death in November 1814 made him the second VP to die in office. The office remained unfilled until the Inauguration of March 1817.

Daniel D. Tompkins (1817 to 1825). Born in Scarsdale, New York, in 1774, Mr. Tompkins practiced law before serving as governor of New York from 1807 to 1817. His governorship included the entire War of 1812, when British troops invaded the USA. During the war, he often spent his own money to equip and finance the state’s militia, when the legislature refused to approve the necessary funds or was not in session. He became the sixth vice-president in the 1816 election and served for both terms of James Monroe’s presidency – becoming the only 19th century VP to serve two full terms for the same president. The strain of the war broke his health, and his military spending had left him financially ruined. He fell into alcoholism and failed to re-establish fiscal solvency, despite winning partial federal reimbursement in 1823. He died 99 days after leaving the vice-presidency, at the age of 50.

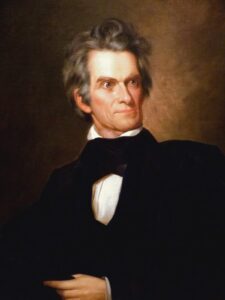

John C. Calhoun (1825 to 1832). Born in South Carolina in 1782, Mr. Calhoun served as our seventh vice president under President John Quincy Adams (1825 to 1829) and President Andrew Jackson (1829 to 1832). He strongly defended American slavery and sought to protect white Southerners’ interests. Mr. Calhoun’s political career began with his election to the House of Representatives in 1810. As a leader of the “war hawk” faction he strongly supported the War of 1812. During his service as Secretary of War under President James Monroe, he reorganized and modernized the War Department. In his early career Mr. Calhoun favored a strong federal government and protective tariffs, but in the late 1820s he became a proponent of states’ rights, limited government and opposition to high tariffs. He also came to regard acceptance of those policies as a condition for the South’s continuation in the Union. Ultimately his beliefs heavily influenced Southern secession in 1860 and 1861. He was a candidate for the presidency in 1824, but after failing to gain support, he agreed to be a vice-presidential candidate. The Electoral College elected him vice president, and he served under both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, who defeated Mr. Adams in 1828. In 1832, with only a few months remaining in his second VP term, Mr. Calhoun became the first vice president to resign from the office. In that same year he was elected to the Senate. Mr. Calhoun later served as Secretary of State under President John Tyler, from 1844 to 1845. In that role he supported the annexation of Texas as a means for advancing slavery. He also helped to settle the Oregon boundary dispute with Britain. In 1844 he tried for the Democratic Party nomination for the presidency, but lost to surprise nominee James K. Polk, who won the general election. Mr. Calhoun then returned to the Senate, where he opposed the Mexican War, the Wilmot Proviso, and the Compromise of 1850 before he died of tuberculosis in 1850. He often served as a virtual independent who aligned, as needed, with Democrats and Whigs.

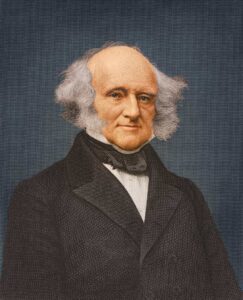

Martin van Buren (1833 to 1837). Born in 1782 in Kinderhook, New York, where most residents spoke Dutch as their primary language, Mr. van Buren is the only president to have spoken English as a second language. Trained as a lawyer, he entered politics as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, won a seat in the New York State Senate, and was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1821. As the leader of the Bucktails faction of the party, Van Buren established the political machine known as the Albany Regency. He ran successfully for governor of New York in 1828, but he resigned shortly after Andrew Jackson was inaugurated so he could accept an appointment as Secretary of State. In that office Mr. van Buren was a key Jackson advisor. He also built an organizational structure for the emerging Democratic Party. Later he was ambassador to Great Britain. President Jackson’s asked the Democratic Convention to nominate Mr. Van Buren for vice president in the 1832 election, and he took office after the Democratic ticket won. Following his vice-presidential term he won the presidency in 1836 against divided Whig opponents – serving from 1837 to 1841. He lost re-election in 1840 and failed to win the Democratic nomination in 1844. Later in his life, Mr. van Buren emerged as an elder statesman and an anti-slavery leader. He died in 1862. (He was the first of three presidents with Dutch ancestry.)

John Tyler (1841). Born in 1790 into a prominent slaveholding Virginia family, Mr. Taylor became a national figure at a time of political upheaval in the 1820s. The Whig Party ticket of William Henry Harrison and Mr. Tyler defeated President van Buren in the 1840 election under the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler too.” Mr. Tyler served as vice-president for only one month during the brief presidency of Mr. Harrison, who had delivered a two-hour speech, standing bareheaded in cold rain during his Inauguration on March 4, 1841. This exposure caused him to contract pneumonia, from which he died on April 4th. His death elevated Mr. Tyler to the presidency, where he served until 1845. Upon assuming the presidency Mr. Tyler signed into law some of the Whig-controlled Congress’s bills, but as a strict constructionist he vetoed the party’s bills to create a national bank and raise tariff rates. He believed that the president, rather than Congress, should set policy, and he sought to bypass the Whig establishment led by Senator Henry Clay. Almost all of Mr. Tyler’s cabinet resigned shortly into his term. The Whigs expelled him from the party and dubbed him “His Accidency.” (They played rough in those days, too.) John Tyler was the first president to have his veto of legislation overridden by Congress. He faced a stalemate on domestic policy, but his foreign-policy achievements included the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with Britain and the Treaty of Wanghia with China. Mr. Tyler believed in Manifest Destiny and saw the annexation of Texas as economically and internationally advantageous to the USA. He signed a bill offering Texas statehood, just before leaving office. The vice-presidency remained vacant until George Dallas took office with James K. Polk in 1845. After serving out his inherited term as president, Mr. Tyler lived until 1862.

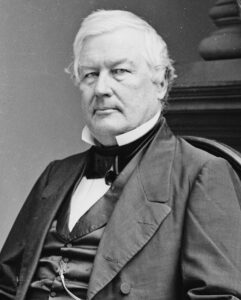

Millard Fillmore (1849-1850). Born into a very poor family in the Finger Lakes region of New York in 1800, Mr. Fillmore had very little formal schooling. Nevertheless, he became a lawyer and gained prominence in the Buffalo area as an attorney and politician. He was elected to the New York Assembly in 1828 and the House of Representatives in 1832. Then he joined the Whig Party ticket in the 1848 election and became vice-president when General Zachary Taylor was elected president. The general had become a national hero because of his victories in the Mexican War, so he governed from only a vague political philosophy. His principal concentration during his 16 months in office was preserving the Union. Mr. Fillmore took office as president when the general died of a severe stomach ailment in July 1850. Mr. Taylor had mostly ignored him, but upon taking office President Fillmore dismissed Taylor’s cabinet and pushed Congress to pass the Compromise of 1850, which led to a brief truce in the battle over the expansion of slavery. The Fugitive Slave Act, which expedited the return of escaped slaves to those who claimed ownership, was a controversial part of the Compromise. Fillmore felt duty-bound to enforce it, although it damaged him and the Whig Party politically – the Party being torn between its Northern and Southern factions. In foreign policy, he supported U.S. Naval expeditions to open trade in Japan and opposed French designs on Hawaii. He failed to win the Whig nomination for the presidency in 1852. Following the breakup of the Whig Party, Mr. Fillmore ran for the presidency as a candidate of the American Party in 1856, but he won only Maryland. When the Southern secessions occurred in 1860 and ’61, he advocated restoring the Union by force but opposed President Lincoln’s war policies. Mr. Fillmore died in 1874. During his presidency the vice-presidential office remained vacant until March 4, 1853, when William King took office as President Franklin Pierce’s vice-president.

*********

To conclude this article I’ll list a few summary-comments on each of those VPs.

- John Adams – took office with no weight of expectations except as second-chair to the already legendary George Washington. He seemed to become president almost as a matter of course.

- Thomas Jefferson – the only VP whose party was not the same as the president’s. He continued the custom of the VP gaining the presidency.

- Aaron Burr – his bitterness over losing the presidency to Jefferson led him to kill Hamilton. It finished his political career. (The public actually disapproved of killing one’s political opponents.)

- George Clinton – vice president under two presidents. Respected statesman. Might have become president but died in office.

- Elbridge Gerry – second of James Madison’s VPs to die in office. (The job might have been a little tougher than it looked. And it was an unhealthy era.)

- Daniel D. Tompkins – a true patriot who broke his health and ruined his finances defending his state as governor, during the War of 1812. His two full terms as James Monroe’s VP made him the only 19th century VP to serve two full terms for the same president.

- John C. Calhoun – vice-president for John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson’s first term. Resigned from office to run for US senator. Respected statesman; pro-slavery advocate. Preached views that formed the rationale for secession.

- Martin van Buren – New York Dutchman, anti-slavery statesman. Vice-president for Andrew Jackson’s second term. Elected president when Whig Party dissolved. (Won the competition for Wildest Hair before hair became a presidential issue.)

- John Tyler – Served only one month as vice-president. First VP to ascend to the presidency on the death of a president: complete political surprise, resulting in the resignation of William Harrison’s Cabinet. Much contention. Political opponents called him “His Accidency.”

- Millard Fillmore – served only 16 months as Zachary Taylor’s VP; became another surprise president. Fired Taylor’s Cabinet; strong anti-slavery advocate in decade preceding the Civil War.

It’s easy to see how disruptive it was when a previously ignored (and not much respected) vice-president suddenly became president, carrying a briefcase chock-full of his own agenda for the direction of the country. The vice-presidency is not a trivial office. This is something to keep in mind today.

In another article we’ll look at some later VPs, with an eye to how they affected the nation’s political tone and attitudes.

2 comments

So what you’re saying is: let’s have us a good old fashioned duel?

Washington apparently thought little of Adams. When he, Washington, wanted to discuss important matters with someone he deliberately excluded Adams. John Nance Gardiner is alleged to have said that the VP office is “not worth a bucket of warm spit”.