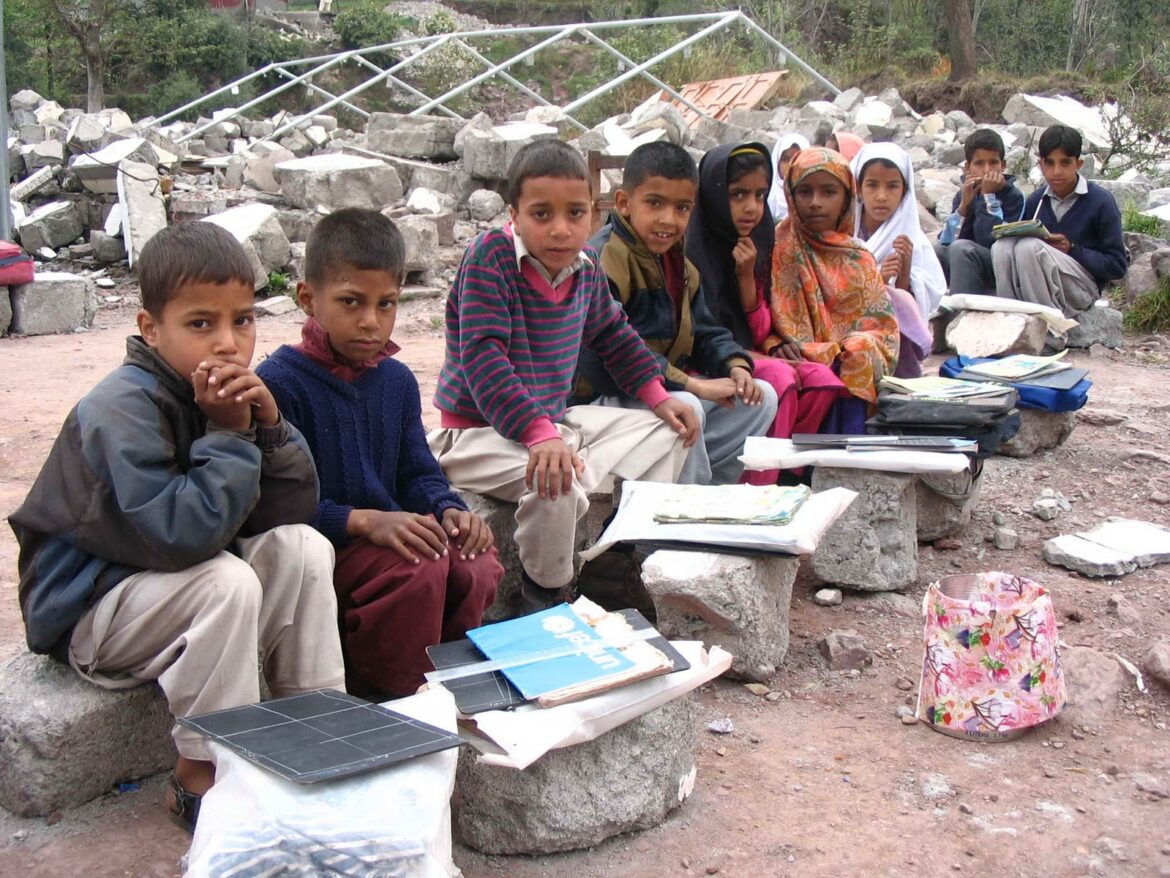

Once there was a group of very poor people who couldn’t read or write. Some attended church, but their illiteracy kept them from joining fully in worship activities. Certain people who saw this wanted to help the illiterate people learn to read. Others scoffed, saying this was unnecessary – that the illiterates could follow the church services just by hearing.

The literacy-advocates thought this argument ridiculous, so they started teaching the poor folk to read and write. An informal movement arose to help many become literate and better themselves, both socially and financially. Then teaching-advocates noticed that others in the land also lacked literacy. This included children living almost wild in the great cities. The literacy movement expanded to teach those children also. It was, at its heart, a missionary effort.

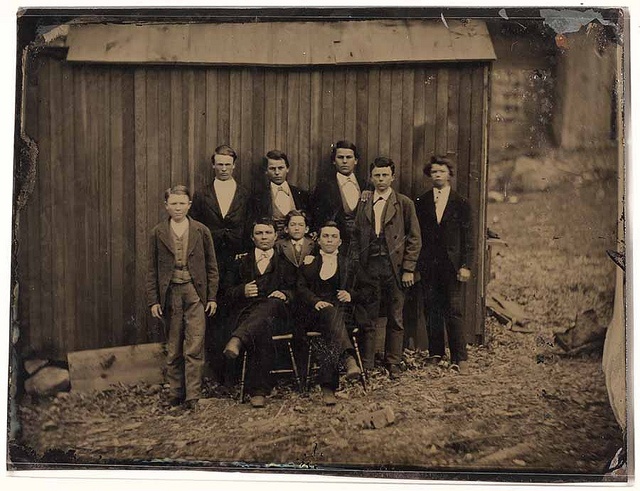

In the cities, the movement established “schools” that met on Sundays because it was the day of the week when most commerce ceased and volunteers could help. All children were invited to take reading, writing and Bible-study instruction. Classes were stratified according to students’ literacy-levels. In time, the movement brought thousands of children to faith. The spiritual influence of these children changed the direction of their nation for many decades to come.

This curious story, which might seem somewhat far-fetched, actually happened – not far across the seas, but in the USA. At the start, the poor, illiterate people were slaves who embraced Christianity early in the nineteenth century. Both white and colored Christians who cared about their spiritual growth and temporal welfare helped thousands become literate.

After the Civil War, the literacy movement helped former slaves, but also expanded to cities where many children lived on the streets. The schools established to teach them were called Sunday Schools. Thousands of children became literate, studied the Bible, and became people of faith. Their Christian influence persists down to the present day. They changed America. But it was the founders of the Sunday Schools whose vision and faith in action made the difference.

Millions of children (like me), from ordinary middle-class families, grew up attending Sunday School. Most of us never knew that the Sunday Schools’ original purpose was helping children whose lives were far different from ours. The Sunday Schools literacy movement is one of America’s great, untold stories. The country would be a different place, had it not happened.

Some readers of my column know that the story of the Sunday Schools movement is one of my favorite topics. I never tire of retelling how it changed the country. One reason I keep rehearsing it is that I hope to see a new “literacy” movement carried forward by churches across the country.

I see two needs demanding this kind of literacy-revival today. The first is language-literacy, like that needed by nineteenth-century America. Although free public education is available to most children, millions still read poorly or not at all. Many are children of immigrants – both legal and illegal. For various reasons – including misguided political efforts to keep immigrants in their native tongues – many immigrant children have poor English skills. This retards their progress in school and helps relegate them to permanent underclass status. A serious societal crime is being committed right in front of us.

But illiteracy is not just an “immigrant” problem. Many native-born Americans also read poorly – some hardly at all. Their schools and families have failed them. Without literacy, they’re headed for the same underclass status as English-challenged immigrants.

An initiative to bring all children – and even some adults – up to proper literacy-levels would change many lives and energize the country. True, it might wreck the political plans of some, and ruin the exploitive economic plans of others. But those fools will have to get over it. Of all possible waste, the waste of human capital is the least tolerable.

The other prong of the new literacy movement should be musical. Many readers will wonder why. Who cares if people are “musically literate?” Besides, what does it mean?

“Music-literacy” means that one can read, understand, and apply the written notation of music. A person “literate” in music knows how to apply printed musical notation to produce actual music. He can sing a song from printed musical copy. This skill – which seems daunting to moderns because it is so little taught – was once in the “toolkit” of most educated people.

I learned to read music in the fifth grade of our public school, where our teachers took musical instruction very seriously. Students were expected to master musical notation – e.g., sharps, flats, note-values, the staff, the key-signature, etc. – and use it in singing from a songbook. This expectation was independent of whether one possessed actual singing talent – in the same way that we all learned to play various sports in physical education class, whether or not we had real athletic talent. Ditto for math, science, reading, writing, etc.

Schools taught important skills to all students without determining who should get specific instruction because of perceived talent. The talent-rule would be thought absurd if applied generally. Yet this is widely done with respect to music and the arts. Children with musical talent receive specific instruction that enables music-literacy. But many others end up getting little or no musical instruction in school, unless their families see to it.

I saw a TV-clip of former Arkansas Governor (and presidential candidate) Mike Huckabee speaking to some Virginia high school students about the importance of artistic and musical instruction. His strong advocacy – as a musician, himself – of this aspect of education was very impressive. He called it “foundational” – not merely “ornamental” – for doing creative work in myriad fields of endeavor, including science and technology. Mr. Huckabee’s forceful, reasoned advocacy had the ring of truth. My own experience also validates his claim. Many of my past teachers and colleagues in mathematics and the sciences were also accomplished musicians.

That we have lost touch with music-literacy shows up in places like sports events, where “singing” the national anthem (if it’s done at all) sounds like an amorphous drone. (If you’re actually singing, you’ll probably be doing a solo in your section of the crowd.) Printed music-copy and hymnbooks have disappeared from many churches because people can’t read music, or are thought unable to do so by church leaders. And we have all heard those pathetic, impromptu choruses of “Happy Birthday,” with everyone singing in a different key.

These instances aren’t the problem, though; they are indicators of the problem. Better singing of Happy Birthday isn’t the need. What’s needed is teaching of music-literacy. Those indicators will show if we’re making any progress. But there’s more to it than just being musically literate.

In our contemporary culture, singing has gone from something you do to something you listen to. Poets say music comes out of the heart, signaling joy inside the person. When joy is absent, there is no song. And if that condition is widespread enough, singing becomes de-emphasized. Try to think of when you were last in a public gathering where the crowd sang together as though they really meant it.

At the open-air Baccalaureate Service for my public high school graduation in 1960, our entire class of 700 rose and un-self-consciously sang, “God be with you till we meet again” in a stirring benediction chorus. Classmates wept openly and embraced as the words “Till we meet at Jesus’ feet” rang out in the June evening. I shall never forget the sound. Emotion still sweeps over me whenever I recall it.

This great, two-pronged literacy initiative is waiting to be embraced by Americans of faith and social conscience. I believe its time has come. Certainly, the need is very great. Will churches again spearhead it, as they did in the nineteenth century? I hope and pray that it will be so.

“I sing the mighty power of God, that made the mountains rise,

That spread the flowing seas abroad, and built the lofty skies.

I sing the wisdom that ordained the sun to rule the day;

The moon shines full at His command, and all the stars obey.”

(Isaac Watts, 1715)