Coming through a divisive political environment, as we are, it’s sometimes difficult to remember that our distinctly American culture once included attitudes and practices that helped to unite us. I was reminded of that recently, when I visited my sister, Kelly, who lives in a charming Northern Virginia community of small houses situated on ¼-acre lots. Once they were called GS-11 bungalows, as many 1950s and ‘60s mid-level government workers lived and raised families in those little houses.

Kelly, now retired, has turned her back yard into a small vegetable farm, and every fall Farmer Kelly – now graduated from her data-processing career – prepares a “harvest home luncheon,” to which all local members of our family are invited. It’s a very friendly occasion, featuring fond memories of Harvest Home church services in our childhood, and the singing of old hymns like “Bringing in the Sheaves,” “Come, Ye Thankful People Come,” “Bless This House” and “We Are One in the Bond of Love.”

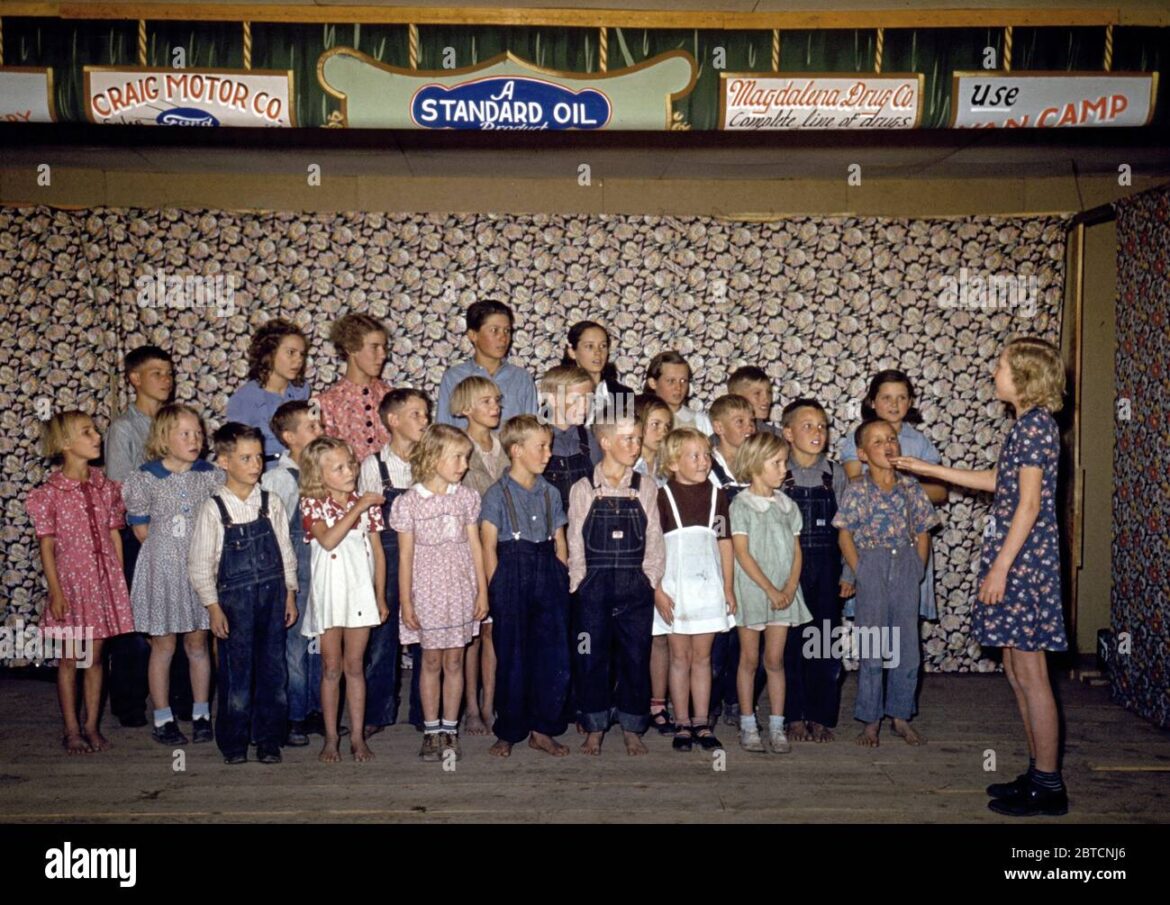

Recent luncheons, shared by members of my musical family, reminded me of how valuable music has been to our lives, and how lucky we were to grow up in the 1940s and ‘50s when public schools still taught music at a meaningful level. We didn’t just sing “It’s a Small World After All” off key, 500 times. Instead, we learned the elements of musical notation, including the key signature, the time-values of notes, the positions in the musical staff (A, B, C, etc.), the names of the octave-scale (doh-re-mi-fah-sol-lah-ti-doh) and the meanings of rests and dynamics-notations (piano, forte, fortissimo, mezzo-piano, etc.)

We were expected to put this teaching to use when we sang in class. My fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Brown, would prowl the aisles of our classroom, brandishing her ruler like a swagger-stick, as we sang from our songbooks. When she found someone wandering from the song’s rhythm, her ruler would crash down on the slacker’s desk – fearsomely beating the time, as the offender struggled to regain his place in the song and keep the time properly.

Despite this Prussian approach to teaching music (or perhaps because of it), my peers and I reached our teens with some competence in reading music and singing. A few of us became public singers, but we could all read music and have a good chance of being able to sing a song – particularly if some instrumental accompaniment helped us along.

One of our fond memories was our Junior High music teacher, Miss Ruh – a commanding lady who stood about 4’8” tall. (Even at age 12 we towered over her.) Her teaching career stretched back to 1915. Because many students’ parents were her students in years past, she could command athletes and other unlikely males to join her school choirs. If her direct invitation didn’t succeed, she would call the student’s family to exert pressure indirectly. She knew that most students had the musical skills they needed to participate in group-singing.

Miss Ruh was a joyful character who loved all kinds of music. Her rollicking piano-accompaniment to World War I songs, like “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” spurred us to lusty singing. She also taught the school’s Alma Mater in class. (Imagine that today.) And she took time to explain the school motto – Personal Responsibility. I realize that I’m describing another century here. If that school has a motto today, it probably changed long ago to Personal Rights. But I digress…

I relate all this by way of contrast to today. The musical instruction I received is now uncommon in public schools. While singing isn’t entirely gone, teaching students to read music is rare. Some schools have eliminated music teachers altogether, so any musical instruction there involves teachers who may or may not be musically educated. Student choirs are a vanishing species. With few exceptions, high school choirs attract girls, but few boys. No self-respecting jock would be seen anywhere near a school choir. Even in my own college days I was the only football player in the choir.

An important cultural shift has occurred while we weren’t paying attention – or maybe too many of us just didn’t care. Singing today is mostly something you listen to, not something you do. If you’ve attended a professional sports event lately, you’ll know what I mean. When the crowd sings the National Anthem – if that even happens – you’ll be doing a solo in your area of the stands. Around you, people will be mumbling or not singing at all – producing a kind of amorphous drone behind the soloist. It’s pathetic, really. (Wags suggest “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” as the new national anthem because more people can sing it.)

I also grew up in a church with a strong musical tradition. I tell my grandchildren how those old Pennsylvanians sang the Songs of Zion – often in both Pennsylvania-Dutch and English – with joy and conviction. Advantageous genes (Welsh, Jewish, Irish) helped me to become a real singer. My public school education and the church singing enhanced that genetic gift. Famous singers like George Beverly Shea and Amy Grant have also mentioned that they learned to read music and sing in church.

Today the listening-not-singing paradigm has even invaded the country’s last bastion of real singing: Protestant churches. Contrasted with my own youth, when we eagerly read and sang hymns and gospel songs from an early age, many of today’s churches are a musical wasteland. Because younger people are often musically illiterate, church leaders tend to assume that no one can read music. This has consigned hymnals and other music-copy to the church storage-closet.

“Congregational singing” in many church-services now consists of “praise and worship songs.” These are led by a worship leader and backed up by a “worship team” of guitar-strummers and jiving singers of various skill-levels. They can be fun to watch, but you’re left wondering what we’re really trying to do. A young neighbor agreed. She said, “I like church to feel like church, not a night-club.”

In fact, the worship-team presentation isn’t congregational singing at all. It’s a performance. Amplification creates an “acoustic illusion” of widespread singing, but the team does most of the real singing, since they have music-copy. Words might be projected on a big screen or printed in bulletin-inserts, but the congregation sees no sharps, flats, clefs or key signatures.

With this new musical style taking hold, the great hymns of the Christian Faith are fading away because of neglect. Hymns like “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross” – sometimes called the greatest hymn in the English Language – are unknown to many young people. Abbreviated ditties written in contemporary style – often in difficult meter – are the new norm. Even trained singers can have difficulty sight-reading them from printed music. But ordinary worshippers struggling with unfamiliar tunes seeing words only, find it hopeless. That same neighbor observed that church songs are no longer “singer friendly.”

A family we know left their church after its leaders adopted an exclusively contemporary style of worship. This included a crash-bang-alakazam rock band, a jiving praise team, and removal of all hymnals and copies of the Bible from the pews. Printed music for the “praise songs” was not furnished. It was a worship-segment in which the congregation – seeing words only – was not expected to participate to any significant degree. Many congregations are struggling similarly over music styles and congregational participation.

On the no-music-copy issue, church leaders typically cite modern worshippers’ music-illiteracy. But their argument is only anecdotal. They offer no data showing whether the illiteracy story is true, or how widespread it is. The new worship axioms are –

- People can’t read music anymore;

- This condition is irreversible;

- Even if it were reversible, the church has no role in changing it;

- Modern people are bored with the “old songs” anyway;

- “7-11 music” (seven words sung eleven times) suits modern musical tastes perfectly.

Non-churchgoers might wonder why I’m hitting a topic that they think has little to do with them. But I suggest that it actually does affect all 21st-century Americans. In an earlier column I argued that the loss of a lighthearted, humorous perspective was a danger-sign for our culture. Just so, I would say that the loss of singing indicates a serious degeneration of our society. The erosion of music teaching has contributed to this problem, since the loss of musical skills means people will sing less. This has diminished public singing in our culture. It’s not a wholesome result.

Poets say music expresses joy that comes out of the heart. When joy is absent, there is no song. And if that condition is widespread enough, singing becomes de-emphasized. Try to think of when you last attended a public gathering where the crowd sang together as though it really meant something.

At the open-air Baccalaureate Service for my public high school graduation in 1960, our entire class of 700 rose and sang, “God be with you till we meet again” in a stirring benediction chorus. Classmates wept and embraced as the words “Till we meet at Jesus’ feet” soared out into the June evening. I shall never forget the sound. Emotion still sweeps over me whenever I recall it.

As a boy I listened to my father singing along with the radio at his workbench. He wasn’t a trained singer, but he had a fine, natural Welsh voice. His workday was long. His house was full of noisy kids. He drove an old car and had very little money in his pocket. Our possessions were meager, contrasted with the bounty that young people have today. Yet music flowed out of him because he was pleased with his life, and his heart was filled with joy and love.

In the Lord’s Providence, Pop taught me the joy of singing and an optimism about life. My children learned these attitudes and skills from me and their mother. Today I hear them singing in their homes and cars, during the joys and challenges of their lives. And their children are doing the same. Singing is being passed on in a joyful heritage from generation to generation.

But around us our culture is forgetting this marvelous gift. We hear professional singers everywhere – including in our churches – but many people think it’s something they can’t do. This situation must be changed. Singing has been a key part of the American character, and we must not lose it.

The road back might be a long one because only a few old fuddy-duddies like me even see a problem. Gradually, though, people are realizing that singing was something that made our culture unique and grand. They want to retrieve it.

In north Georgia, our son and his family searched until they found an Evangelical church that still sang the old hymns. “We wanted our children to know those songs,” they said. That church was filled with young families of like mind.

To restore singing in our culture, we need to restore the musical building blocks in our schools and churches. These institutions will lead the way to rediscovering singing. The great, swelling choruses of “God Bless America” and the National Anthem at recent political rallies show that Americans are finding the road back. I urge my readers to pray for that movement to gain in strength. It will help us reclaim the America we once knew.

“Without a song, the day would never end;

Without a song, the road would never bend;

When things go wrong, a man ain’t got a friend,

Without a song.” 1

*******

- From the musical Great Day; lyrics by William Rose and Edward Eliscu; 1929.