Last week we reviewed some aspects of how the Politics of War have changed in our country. In this article we’ll briefly examine how some important moral and ethical factors connected with war have changed over the past century.

The Disappearance of Evil.

As American culture has become less religious, the notion of evil has receded into the misty past. Indeed, what we once called evil has become almost normalized. Behaviors which formerly gave evildoers long terms in prison or even cost them their lives, under the law’s judgments, are now either minimally punished or called “alternate lifestyles.”

Today, unregenerate sexual predators live among us, serially victimizing children. If caught and convicted, they go to prison, serve part or all of their sentences, and then are released back into society. Communities try to learn who they are, but are often blocked by authorities concerned for criminals’ “privacy.” States and localities pass laws to identify habitual child-predators, but some courts overturn the statutes. Perpetrators of repeated perversions are no longer called “deviants.”

Occasionally, a crime captures the attention of the media, as in the case of a young woman who disappeared while vacationing in Aruba. The media obsessed for weeks on her kidnapping and probable murder. Certainly, it was a wretched business. Meanwhile, other equally despicable crimes were ignored or aired only briefly. Two homosexual men in Arkansas raped a 13-year-old boy repeatedly. He suffocated when they stuffed underwear in his mouth to stifle his screams. The media all but ignored the incident. The term “evil” did not appear in any news reports I saw.

Media disinterest in identifying and fighting evil now extends to terrorist violence committed by foreign agents, here and abroad. Increasingly, media commentators call such agents “freedom fighters” who are disadvantaged “losers in the lottery of life.” Even our American media now call people “bombers” or “militants,” instead of “terrorists,” when they blow up civilians. “Terror” and “evil” have gone missing from our lexicon.

This is not an analysis of what happened to evil, of course. It’s merely an observation that we no longer think of fighting crime and terror in terms of good versus evil. We have “defined evil down,” to paraphrase Senator Daniel P. Moynihan’s insightful observation.

Perhaps more than most peoples, Americans need to that they are in mortal combat against Evil when they go to war. This explains why the Vietnam War was so hard to sell. Many of our people – particularly young people – could not see the quirky little Vietcong “freedom fighters” as evil. They grew up on Ernest Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and the romantic communists fighting Franco and the fascists in Spain. The “evil” story wouldn’t play.

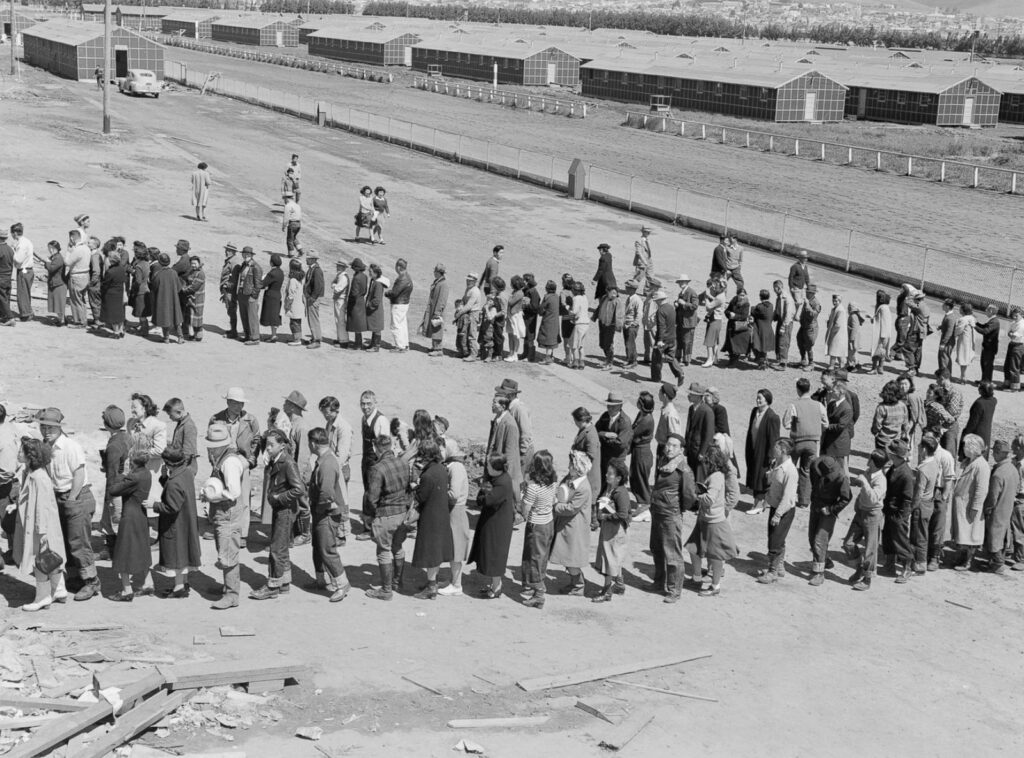

In World War II, of course, evil didn’t need much selling. Thousands of young men lined up outside recruiting stations on December 8, 1941. The Japanese motivated us with the “dastardly” Pearl Harbor attack and the horrible Bataan Death March. Word was already trickling out about mass gassings at Nazi death camps in Eastern Europe. Americans didn’t have to be persuaded that these enemies were serious bad guys that we had to crush. We knew they were evil. This conviction enabled us to finish Japan with the A-bomb. It’s nearly impossible to envision such an action today. Unless we are a-bombed first, the public would not countenance it.

To defeat terrorism we’ll need to realize that people who masquerade as “religious,” while blowing up buildings and beheading innocent people, are not misunderstood. They’re evil.

The Feminization of Culture.

Some readers might dislike this section – perhaps imagining that I want to roll back opportunities for women. But I mean no such thing. I have a daughter, four granddaughters, and a great-granddaughter. Of course, I want them to have every possible opportunity to pursue occupations that suit them. This isn’t about the suppression of women. It’s about oppression of boys.

On the premise that girls were being shortchanged and denied opportunities, feminists have mounted a fierce fifty-year campaign to make education “girl-friendly.” Whether this was really needed is open to question. Some female colleagues who worked with me in computing and engineering told of constrained educational opportunities – mostly due to racial discrimination. But I grew up during the 1950s when girls supposedly were being held back. I knew some pretty smart girls, and I don’t remember any of them being kept from what they wanted to do.

However things were (or weren’t) in the “bad old days,” schools have unquestionably bowed to feminist pressure and become feminized to the point where boyish behavior is being actively squelched. Christina Hoff Sommers, author of The War Against Boys: How Misguided Feminism is Harming our Young Men, says educators are treating boyhood as a “pathology.” The guiding principle, she says, is: “Girls good, boys bad.” The rough, active play of boys is discouraged. Even recess has been abolished at some schools. (Nice idea, when childhood obesity is a major societal concern.) Significant numbers of schoolboys are being given Ritalin for “hyperactivity.”

Dr. James Dobson says boys typically show up in a loud, active group. They build something, then knock it down and run off to do something else. All is action, vigor, energy. My sons liked to roughhouse, run and play games that tested their strength. Their sons are the same. This, of course, is what soldiers do. To the extent that boys are kept from such behavior, they are being conditioned away from the active young manhood our military services need.

Today, many people would see this as not only a non-problem but as a positive development. They would be glad if boys don’t grow into men who can be good soldiers. That’s all very well. I understand the sentiment. No one wants his son or brother or father to die as a soldier.

But as World War II showed us, there comes a time when a nation must fight to survive. When that time arrives, we shall need young men who can step up to the task. Notwithstanding the delusions of feminists, young women cannot fill that role. They generally lack the strength (and often the temperament) to be combat soldiers. Only strong, confident young men can do the job.

Other contemporary factors bear on this problem. We can’t discuss them in much detail, but they merit some mention. One is the strong homosexual influence in the popular culture. Cinema and television are saturated with the gay man as the ideal male – sensitive, caring, good looking, well-turned-out, tolerant, and far more intelligent and capable than the typical boorish heterosexual male. Smooth-chested – in the gay style – is the way we want our male heroes to look today.

And now, going well beyond the gay-craze, we have the transgender-craze which advocates surgical removal of healthy male organs to convert healthy boys into supposedly happy and fulfilled “girls” – and, to a lesser extent, converts healthy young girls into girly-boys. This perverse movement is enthusiastically joined by doctors who anticipate the megabucks they will earn from these Nazi-esque operations. The movement also enjoys political support, reaching all the way to the White House. But its product will be only emasculated eunuchs and girls pretending to be boys. Neither of these ruined physical desecrations will grow into functional men or women, and neither will ever produce new offspring. Their line will be forever cut off.

The obverse of the gay image is now the strong, invincible female – nemesis of the depraved, disgusting male. The final film incarnation of the Karate Kid was a Viking-like girl who defends her weaker, less capable man and defeats his enemies. Even the newest movie about the love-bug, “Herbie,” features a girl who drives Herbie to victory over her swinish male rival.

The media hope excellent female golfers like Michelle Wie can win PGA tournaments, but reality is stubbornly otherwise. Girls are not as strong as boys. Women can’t make the football team. Real life is not a movie. This make-believe helps neither young women nor the young men we might one day depend on to fight the nation’s real, vicious (and mostly male) enemies.

Loss of the Citizen-soldier.

Young men of my generation rejoiced when the draft ended and the all-volunteer army began. For a confluence of reasons I was not drafted during the Vietnam era, but I knew a lot of guys who were. Some of them came home in wooden boxes. Plenty more came home that way from Europe, the South Pacific, Italy, North Africa and Korea – or are buried in those far-away places. Nobody my age or older gets misty about the good old draft.

My dad was drafted in 1944, soon after the Normandy landings. Pop joined the Fourth Division in France – a replacement for some soldier who fell or was disabled either in the landings or during the battles to bust out of Cherbourg. He served a year and a half: caught pneumonia camping in the Belgian mud; missed some of the heaviest fighting in the Hürtgen Forest and the Bulge; and came home in 1945 to train for the invasion of Japan. The latter never happened because the mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki convinced Emperor Hirohito that it was time for Japan to surrender.

I never heard Pop complain about the draft or say he wished he hadn’t had to serve. He didn’t love the Army, but he didn’t hate it, either. He spoke of his comrades with humor and affection, and kept in touch with some. He always mentioned Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. – commander of the Fourth Division – in terms of the greatest respect and admiration.

What Pop did say about the draft was that it produced soldiers who wanted to get the thing done as quickly as possible so they could go home. He also thought that the many draftees from all across the country gave the war a broad base of support that motivated the whole country. I recall those blue-star and gold-star banners still hanging in many homes, many years after the war. It was a total national effort. Very few families were untouched by it.

The volunteer army exhibits notable strengths, including aspects that are the opposite of the conscript army. The volunteer army can invest in expensive training for its soldiers, knowing that they will stick around awhile. Volunteers want to be there. They are motivated to high performance because the Army is a career for them, not just something to get away from as quickly as possible.

But the volunteer army has weaknesses, too, as we realized during our first prolonged war-effort since going all-volunteer. One of those weaknesses is that some enlistees pictured only the peacetime army when they joined up. They never expected a war, and were disillusioned about it when it came. Some female soldiers requested discharge when we went to war on terror.

A protracted war – even at the relatively low level of the past action in Iraq – also affected recruiting. An army where you can get killed – it turns out – is a less attractive career choice than an army where the main issues are skills, training, promotion, pay, and benefits. Military leaders have not said so, but one suspects that manpower issues might affect future military strategies and actions in ways never anticipated when the all-volunteer army was originally planned. “Be careful what you wish for,” a wise man once warned.

Conscription was always painful, and an unpopular war made it unsupportable. But there is growing doubt that an all-volunteer armed force can fight a major war. And a two-front war might be impossible without greater strength. That strength might not be achievable with only volunteers. Even North Korea has more men under arms than we do. Thus, in a dangerous world, the citizen-soldier might return. If he does, he will present some formidable political difficulties.

A Diverse Culture.

America has always consisted of diverse elements from all over the world. Certainly that was so during World War II. Diversity has been a source of our national strength.

The difference now is that many immigrants – including millions of illegals now flooding across our borders – come here without expecting to become Americans. They anticipate remaining Mexicans, Saudis, Iranians, etc., who just happen to live in the United States. Instead of “assimilating,” they live within communities of their particular ethnicity, speak their native language, and follow their old customs. Many learn no English. If they can amass sufficient political influence, they might even force employment of their language for business and governmental transactions. This is not your grandfather’s melting pot.

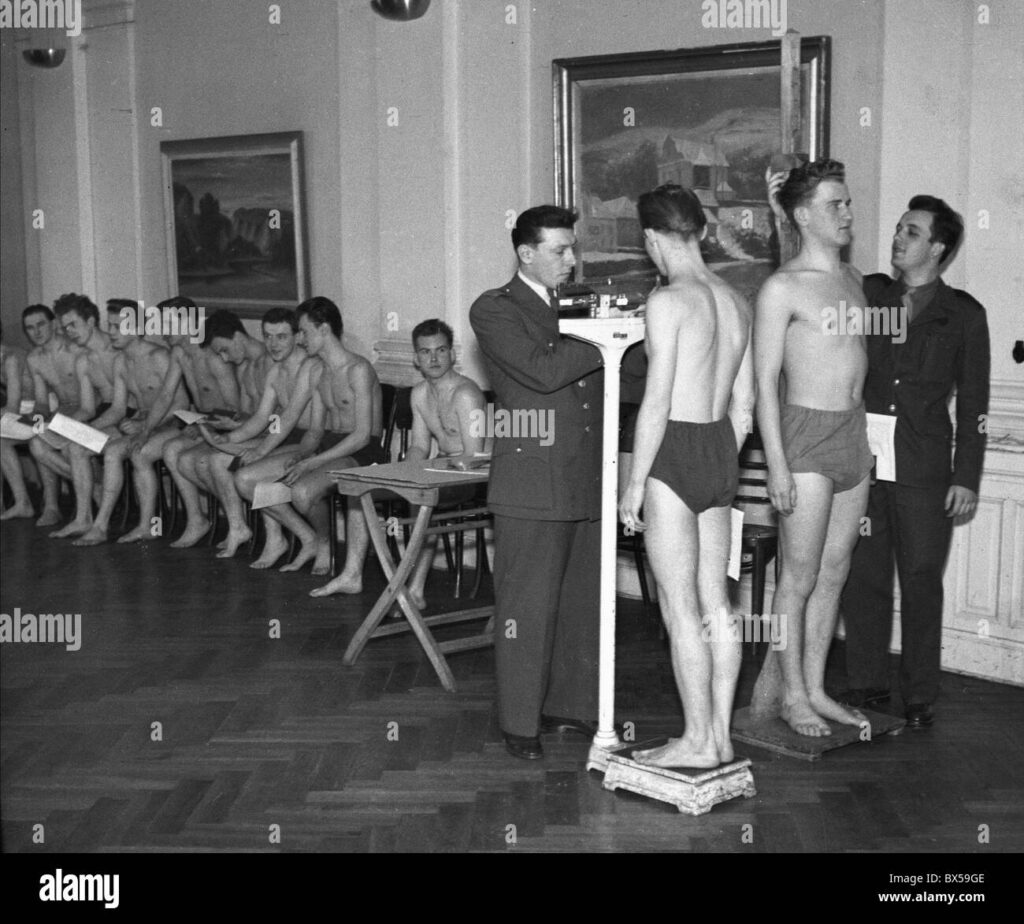

During World War II the USA took the radical step – regretted ever-afterward by sympathetic citizens – of interning west-coast people of Japanese descent in inland camps. Authorities feared that their sympathies might lie with the Japanese instead of their adopted country. The question of whether that assessment was correct has been obscured by later controversy over the internment.

Today, such a policy would be prevented by racial sensibilities and political correctness, even if it were demonstrably clear that certain foreign communities did represent a tangible threat to our security. Indeed, grave suspicion exists that some radical Islamist communities pose such a threat. Until we deal with those factions, our ability to protect the homeland – a fundamental pillar of prosecuting a war successfully – will be degraded. We dealt with that threat decisively (but radically) in World War II. It represents a major difference between then and now.

*******

America has changed in many ways since 1945. We can’t live in the past, but we need to learn from it. Until we do, the War on Terror and other future conflicts will be slow, dangerous going.