During Mr. Trump’s first term the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives created a stir by passing a controversial bill which authorized a radical restructuring of the District of Columbia:

- The Federal District of Columbia – specified by Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 of the U. S. Constitution – would be reduced to a small area containing Federal monuments, the White House, the Capitol Building, the United States Supreme Court Building, and the federal executive, legislative, and judicial office buildings close to the National Mall.

- The balance of the current District of Columbia’s land would be admitted to the Union as the 51st state, to be called “Washington, Douglass Commonwealth.”

The bill’s passage evoked wild cheering from Democrat-partisans, since the new state would probably add a new Democrat representative to the House, plus two Democrats to the Senate. It would also add three new Democrat electors to the Electoral College.

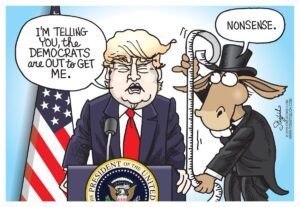

Political analysts noted, however, that the Republican-controlled Senate would not support the bill, and then-president Trump would certainly veto it. Republicans breathed a collective sigh of relief for dodging a dangerous political “bullet.” But Democrats warned that they would get it done after they win the Congress and presidency in a coming election. Unfortunately (for Democrats) that didn’t happen during Mr. Biden’s recent term.

Now, at the start of his second term, Mr. Trump has turned the issue upside-down by floating the radical idea of adopting the entirety of Canada as our 51st state. Journalists and the TV blow-dry cadre – who obviously know little about the Constitution – are reporting the Canada statehood idea as something that Republicans might actually try to do.

But the issue of making the District of Columbia (or Canada) into a new state is not quite as simple as shooting a bill through the Congress and having a compliant president sign it. A little historical background is needed, starting with Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 of the Constitution, which reads:

“Congress shall have power: To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States, and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful Buildings.”

The Constitutional plan calls for creation of a federal district, no more than ten miles square, from land ceded by one or more states to house the U.S. national capital. This happened via the Compromise of 1790, which formed the District of Columbia from land ceded by Maryland and Virginia. The national capital was temporarily relocated from New York to Philadelphia while construction began on homes for the president and the Congress. And in December 1800 the US capital was moved for the final time to Washington, DC. The new District of Columbia was a square, ten miles on a side, oriented as a diamond with its northern and southern vertexes located on the same line of longitude.

In the 1840s the state of Virginia petitioned the federal government for return of that parcel of land which Virginia had ceded to create the District of Columbia, as it was not being used for governmental purposes. That land was then retroceded to Virginia in March 1847 and became Arlington County. The Potomac River became the new southwest boundary of DC.

The Constitution clearly gives Congress the power to reduce the area of the Federal district, as it did in 1847. But should it do so, that land would go back to Maryland, which originally owned it. Congress has no power to create a new state from the territory of an existing state by simply passing legislation. Citizens of an existing state may vote to split off part of their territory to form a new state, as western counties of Virginia did in 1863. Those counties became West Virginia, after Congress voted to admit them into the Union.

The “secession” of West Virginia from the Confederacy – which the Confederate government at the time was bound to honor – was useful to the Union during the Civil War. But today, a similar action by an existing state – e.g., Maryland – would be intensely political and fraught with contentious partisanship. Past Congressional votes to admit new states were unanimous, or nearly so,1 but a vote to admit a new city-sized state, which had formerly been the District of Columbia, would almost certainly spark the Mother of all political battles for both parties.

If successful, such a ploy would open the floodgates to similar efforts all over the country, as numerous states might attempt to multiply their Congressional and electoral influence by splitting themselves into several new states. To say it would end the United States as we know it would be an understatement. It would be a nightmare.

Any change to the Constitution to modify the protocol for admitting new states – an idea also being bandied about – would be a steep uphill climb. A Constitutional amendment requires a 2/3 majority vote in each house of Congress, plus subsequent approval by 38 of the 50 states within the time-limit, if any, established by the Congress. Adopting an amendment which changed the rules for adopting new amendments would also be politically impossible, as ¾ of the states would never approve it.

Some politicians today have been energized and excited by recent presidents’ use of executive orders to do controversial things which a politically polarized Congress would never approve. This has produced a backroom-buzz which imagines that a president might be bold enough to create a new state by a simple executive order, and possibly ruthless enough to disregard the Supreme Court’s counter-ruling.

In other articles I have pointed out the centrality of our unwritten “compact” of governance, which create a structure in which either political party can govern in an orderly fashion. One element of that compact is unquestioning fealty to the text and meaning of the Constitution, whether one agrees with its stipulations or not. A second, equally important element is the agreement by the minority party that the majority party must be allowed space to govern. Orderly governance is rendered impossible without adherence to these elements.

In recent years we came close to complete disorder due to disregard of the compact – a very dangerous situation, not least because our external enemies are watching closely, hoping that we will self-destruct. We need to stop this. Thomas Jefferson’s comment long ago about slavery applies to this issue:

“Like a fire-bell in the night, it woke me and filled me with terror.”

*********

- On March 11, 1959: the Senate voted 75-15 to admit Alaska as the 49th state; the House approved the admittance by 323 to 89 on March 12, 1959. A bill to dissolve the Territory of Hawaii and admit it as the 50th state was enacted by Congress in March 1959 and signed by President Eisenhower. Hawaii became a state on August 21, 1959

2 comments

I think we should form a new state with DC. It should be enlarged to include the suburbs in both Maryland and Virginia. It would include Montgomery and PG counties in MD and Arlington, Fairfax, and Eastern Loudoun in VA . This would have the practical effect of consolidating the transportation system into one state entity. Politically, this works because by carving out Northern Virginia and putting it in DC, Virginia then becomes a solidly red state. This balances out the fact that DC would be a bright blue state.

That would require a change to the Constitution. Leave it alone.