“The problem with Death is that it’s so final…”

I read that somewhere. Actually, I think I wrote it – although I’m surely not the first to make the observation. Death – “natural or not” (as gangster Hyman Roth put it) – has been at the absolute center (or at least the end) of the Human Condition for as long as people have lived on the earth.

Whole libraries of books have been written on this topic, so I won’t try to add to all that wisdom. But I do want to discuss death officially administered by the State. Capital punishment has been practiced as long as societies of people have exercised power over individual conduct. Well within my own lifetime, capital punishment was relatively uncontroversial in the USA. An execution might be mentioned in the morning papers, but it was usually not big news unless the case was sensational in some way. The execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg – the Soviet spies who stole the atomic bomb secrets in the early 1950s – was a notorious spy case. Also, it was unusual for a woman to be executed.

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, 1953

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, 1953

In my boyhood, older people still talked about the Leopold-Leob case of 1924, in which two brilliant and wealthy university students, Nathan Leopold, Jr., and Richard Allen Leob, murdered Bobby Franks, aged 14. (Newspapers of the time called it a “thrill killing.”) They were apprehended and put on trial for first degree murder. Ordinarily, they would have received capital sentences, since their senseless killing of a minor was premeditated and there were no mitigating factors.

But their families retained famous defense lawyer Clarence Darrow, who set a precedent for the future by putting the American criminal justice system on trial for being “retributive” and motivated by vengeance. (“Decent” people evidently didn’t seek retribution for vile crimes like the murder of an innocent boy.) Darrow saved the pair from the electric chair. They were sentenced to life imprisonment “without possibility of parole.” The country was shocked over the lenient verdict, and we were on our way to the non-retributive era of American justice.

Richard Leob was killed in prison by another prisoner, in 1936, but Nathan Leopold continued to serve his sentence. A “genius,” with an IQ above 200, Leopold studied medicine in prison and participated in a medical study in which he was voluntarily infected with malaria. In 1958 he was paroled to serve as a doctor in Puerto Rico, which he did until his death in 1971. Of course, his release superseded the original sentence, which had stipulated “life with no parole.”

The Leopold case demonstrated the unreliability of no-parole sentences, where a prisoner might outlive the societal outrage over his crime. In 1958, Bobby Franks was long-forgotten in his grave, and no one remained to argue for justice for his senseless and outrageous murder. By the nifty ‘50s, we were well into the enlightened age. Retribution had fallen out of fashion – although not completely. No protest was raised when the notorious Nazi, Adolph Eichmann – architect and head-honcho of the Final Solution – was kidnapped in Argentina by Israeli agents, taken to Israel, charged with crimes against humanity, tried, found guilty, and ultimately hanged in 1962. Evidently, neo-enlightenment had its limits.

Leopold and Leobb, 1924

Leopold and Leobb, 1924

Certainly error is possible in a judicial proceeding that orders death for someone accused of a terrible crime. Can we be 100% certain that the person convicted is truly guilty? No, few things can be that certain. If they had to be, generally, we should not have cars, airplanes, complex electronic devices and machines, medicinal drugs, and a host of other accoutrements of our civilization. (Even mousetraps don’t work with 100% reliability.)

Our judicial system has an ancient pedigree. It contains provisions that uninformed people might consider arcane and unnecessary, like the requirement of unimpeachable evidence. But those provisions protect the accused from hearsay, unsupported innuendo, and a rush to judgment fueled by public emotion. When the process is allowed to function as designed, it comes as close as one can probably hope to a correct verdict.

Nevertheless, mistakes can be (and have been) made because of technical limitations, stupidity, incompetence, or outright corruption. Juries can be misled or confused; prosecutors and defense attorneys can make mistakes; so can judges. There are many working parts in a murder trial, and any can fail. Generally, the process can withstand a few malfunctions and still produce a correct result – but not many.

As forensic science and investigative methods have become more sophisticated, errors in some past cases have come to light. Over the years, enough disclosures of verdict-reversing DNA evidence, etc., have accumulated in the public mind to degrade confidence in the judicial process – particularly in capital sentences. This came to a head in 1972, when public revulsion over a “flawed” system produced a Supreme Court ruling which stopped executions in all states and U. S. territories, plus Washington, DC.

The Court lifted its ban in 1976, subject to states’ redrafting of their capital punishment laws. Thereafter, thirty-seven states re-authorized capital punishment, but six of them have since abolished it. Today, nineteen states do not permit it. (Hawaii and Alaska have never allowed it.) Since 1976 there have been 1471 executions in the USA: Texas leads all states with 548 executions since 1976; Virginia had 113; Oklahoma, 112; Florida, 96; Missouri, 88. Sixteen states had fewer than 10 executions. The USA is the only country in the western world which still permits capital punishment.

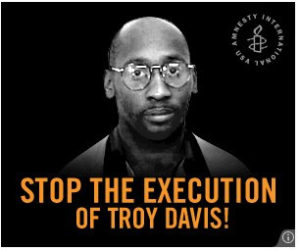

Although capital punishment has a new lease on life (so to speak), it remains controversial, even in states that have re-authorized it. A 2011 case in Georgia reminded us that the public mind is not settled on capital punishment. Troy Davis, 42, was executed by lethal injection after all appeals had been exhausted. He had been convicted of murdering Savannah Police Officer Mark MacPhail in 1989. The case became a cause célèbre for the death-penalty opposition because some witnesses were said to have recanted their original testimonies, creating doubt about the correctness of the verdict. Davis stoutly insisted on his innocence, even at the moment of his death, when he faced the family of murdered Officer MacPhail and told them that he did not kill their “son, father and brother.”

I have no idea whether Troy Davis was innocent of the crime he died for. I don’t oppose a sentence of death for the taking of an innocent life. That punishment is rooted in civilizations that go back thousands of years. It is supported by the Bible, too, in case that counts for anything in today’s societal discourse.

Nevertheless, you don’t have to be very far-left to see that there are problems with the way we apply capital punishment. One of those problems is time. The Davis execution was finally carried out 22 years after his crime. Anti-CP partisans say this provides ample time to uncover potentially exonerating evidence before the sentence is carried out. That could be true, but it also allows time for some witnesses to die and for others’ minds to become clouded. This spurs a kind of rump trial in the media, where evidence can be cherry-picked (or glossed over), and judicial rules can be ignored. If the death-row convict happens to be a racial minority, activists can convert his case into a “civil rights” issue. All of this happened in the Davis case, confusing things even more.

A considerable crowd of protestors held a midnight vigil outside the prison in Jackson, Georgia, where Davis was executed. They held candles and wept as the fatal dose was administered. But I read no accounts of similar demonstrations to mark the tragedy of the foreshortened life of Officer MacPhail. He was long forgotten by (or unknown to) people who were children, or not even born, when his killer(s) pitilessly took his life. This, too, is a result of the long space between crime and sentence. The public outrage is forgotten. Only a few older people can even recall the horror of the wretched deed that ended an innocent person’s life. It becomes easier to concentrate on the state’s taking of the murderer’s life, and the tragedy that represents to his family. There is a reason why the Constitution stipulates that justice needs to be “swift.” Letting so much time elapse, in this way, perverts that justice.

Officer Mark MacPhail

Officer Mark MacPhail

Another significant problem in capital-crime justice is “selective application.” Increasingly, capital sentences are given only for what we call “heinous” crimes. The dictionary defines “heinous” as “hatefully or shockingly evil.” It’s probably a good definition, but where is that found in our legal code? I know of no legal stipulation localizing the death penalty to crimes of this nebulous description.

Prosecutors and judges have unilaterally decided on this new standard for application of capital sentences. But “heinous” is in the eye of the beholder, and can be applied subjectively. As it appears to this observer, “heinous” crimes are murders in which the victim is: a child, a mother of young children, a beautiful (usually white) young woman, a gay person, a policeman, a congressman, a judge, or some other government official. Multiple murders are also considered heinous, although there can be exceptions to this rule when the crime appears to be politically motivated. But if the victim was a shopkeeper, a middle-aged businessman, a truck-driver, a minister, a homeless person, etc., it is unlikely that a capital sentence will be pronounced.

I recall an episode in the old Untouchables TV series, starring Robert Stack as Federal Agent Eliot Ness, in which a gangster was hot for the wife of a dry-cleaning shop owner. When she refused him, he sewed blasting caps into a pair of pants and took them to the shop for hot-pressing. The pressing machine set off the caps and killed the shop-owner. On apprehending the killer, Ness said, “You’ll get the Chair for this, Rocco…”

Things were that way well into my lifetime. Wasting a mere shopkeeper – or anyone – could get the killer a date with the Chair or the gas chamber. But the times have a-changed. If you’re not on the A-list of victims, your murderer will be watching The Days of Our Lives, playing ball in the exercise-yard, and reading up on the law in the prison library, long after you’re in the ground. I’m not the only person in the country who sees this as a problem. We need a reformation of the “system” we have now. Either every human life has value, or none does. And justice needs to be swift.

Eliot Ness

Eliot Ness