By Patrick M. McSweeney & William J. Olson

Although the House had jurisdiction to impeach while President Trump was in office, the Senate has no jurisdiction to conduct a trial because there can be no removal punishment for an individual who is not in office.

The United States Constitution is unambiguous: there are only two punishments that the Senate can impose in an impeachment trial. One is removal from office. The other is a bar on holding future office. These punishments are set out sequentially in the same sentence in Article I, § 3, clause 7. Textually, the bar on future officeholding is ancillary to removal. Thus, since President Trump can no longer be removed, neither can he be disqualified from future service.

Likewise, Article II, § 4 limits the congressional impeachment power to those in office: “The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” Again, there can be no impeachment trial without the possibility of removal.

Also, Article I, § 3, clause 6 provides: “When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.” Because the Constitution only addresses how “the President” shall be tried, the textual inference is that there is no means established to try an individual who is no longer “the President.” That is why Chief Justice Roberts is nowhere to be found.

Lastly, Article I, § 9, clause 3 prohibits bills of attainder and bars the legislature from imposing a penalty without a judicial proceeding and conviction – exactly what the House impeachment asks the Senate to do.

During the trial, arguments for impeachment are being made which may sound constitutional in nature, but are really nothing more than policy arguments. The Democrat impeachment managers have argued that the Senate should be able to try an individual who is no longer in office because otherwise that individual could avoid the consequences of actions committed while in office. That argument fails for two reasons. First, there is no constitutional bar on prosecuting a former officeholder for treason or other crimes after leaving office. Second, the argument is devoid of textual support and based only on a policy preference that cannot add to or modify the text of the Constitution regarding the Senate’s jurisdiction.

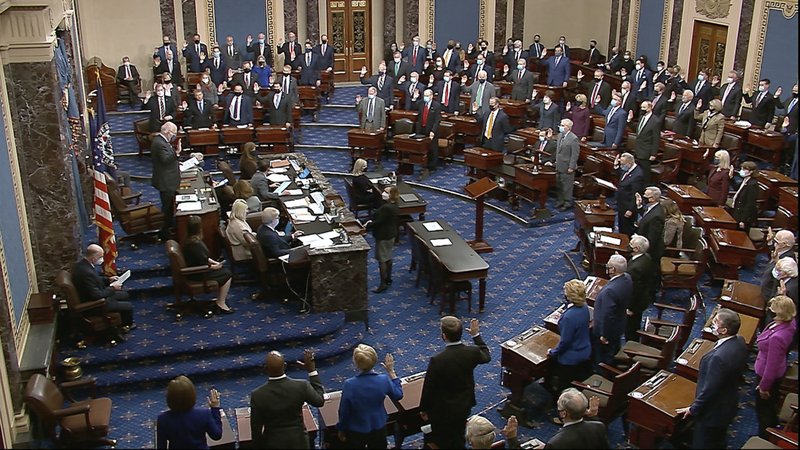

The solemn responsibility and sworn duty of Senators is to follow the United States Constitution. For them to exercise jurisdiction by conducting a trial on a bill of impeachment of an individual who is not in office and cannot be removed from office is itself an abuse of power. Senators allowing the trial to proceed should not be surprised if their actions this week are one day viewed as “disorderly behaviour,” deserving of expulsion under Article I, § 5, clause 2.

Patrick M. McSweeney

McSweeney, Cynkar & Kachouroff, PLLC

William J. Olson

William J. Olson, P.C.