It’s a debate that can never meet anywhere; orthogonal in nature and incapable of resolution.[read_more]

[Note: In light of the war declared by the Supreme Court on both freedom of religion and free speech, it seemed an appropriate time this Independence Day to revisit some of the heroes of our Founding – the Patriot Pastors – and look at the great inheritance passed down to us. I originally wrote this piece several years ago, thinking that the subject and length would have a limited audience. Instead it has been of the most requested pieces I’ve ever written, and I still receive requests for its use. I have retitled the piece, to more accurately describe today’s need! God Bless our Republic, and God make us worthy of this great birthright. -MG]

The ongoing argument, punctuated by occasional wars, is about the organization and purpose of society, and has roiled the Western world’s political and religious thought for centuries – refocused by today’s economic chaos, the rise to power of genuine radicals in both Congress and the permanent government, and the destructive presidency of Barack Obama.

This is the issue of our era just as it is for every era, where one generation’s decision determines not only how they will live, but how their children and grandchildren will live.

It’s the irreducible conflict between liberty and collectivism; free will and authoritarianism; and the origin of individual rights. Should a society be assembled largely by self-interested individuals pursuing their own best purposes and living out their faith; or should the sum of any society be defined and controlled by the power of government for the “common good?”

It’s interesting that the political and the religious are frequently presented as distinct and separate spheres of interest that can never be co-mingled in this debate, but actually they are as close as a hound dog is to a tick: The political class can’t scratch an itch without seeking the imprimatur of religious or moral virtuosity. People of genuine faith simply cannot separate themselves from the affairs of their day lest they cease to be salt and light to the world.

Just as with political conservatives, the orthodox faithful in our churches and synagogues are under withering attack today.

The modern church’s institutional weakness and aggressive emasculation makes it the perfect target.

Everywhere in the crumbling Western democracies the intellectual air is thick with words like fairness, social justice, economic equity, redistribution of wealth, getting a fair share. All of these are street slang used in the all-out war on free will, religious freedom, free markets, and individual responsibility. This assault on individual liberty is so far advanced that many conservative politicians and orthodox religious leaders have been cowed into either adopting the characterizations of the extreme left, or simply ignoring them, leaving the “progressive” agenda uncontested.

Without significant resistance many mainline Christian churches have revived the centuries-old social justice canard, a trend which tragically includes a growing number of churches in the “evangelical community.” And no small numbers of the “progressive” churches are promoting repackaged liberation theology.

So the defense of our most cherished values is reduced to a quiet frustration and the principles for which over a million Americans died to secure, grow increasingly dim – like a fading candle. We’re led by the weakest of the weak, at a time when we desperately need street fighters – both in politics and to defend the faith.

But, this was not always so. In fact, for much of our history, it has been just the opposite. Godly men and women who were fearless, bold, strong and savvy have been central to the American experience.

The American Founding specifically was intricately woven into the American story in large measure by the hands of courageous clergy and congregants of the early Colonial churches; and the battlefields of the Revolutionary War would later drink the sweat and blood of many patriot pastors and their congregations who were among the first to take up arms when the war did come.

The inspiration and grand proposes of the American Founding and subsequently the Constitution come in no small measure straight from the pens and sermons of our early colonial clergy. It was the pastors and ministers who educated and shaped the worldviews of several generations of colonists, preaching on the powerful connection between Biblical truth, the inalienable rights of men, and a just and limited government.

Starting with the first years of the colonial settlements, pastors had a dramatic and consequential place in the American story. In Virginia, prominent ministers were instrumental in the creation in 1619 the House of Burgesses, the first elected legislative body in North America. In Massachusetts, Pilgrim and later Puritan ministers were in the forefront of establishing elected representative governments, and in 1641 the Puritans had a Body of Liberties, a document of individual rights written by Rev. Nathaniel Ward.

Throughout the 1600’s the new colonies led or influenced by Christian ministers established elected governments with defined rights. The English born Anglican turned Puritan minister, Roger Williams came to Massachusetts in 1631, only to be officially banished in 1635 by the Massachusetts Bay Company for his belief in “separatism,” or total religious freedom, and for publically challenging the Company’s right to regulate any religious activity. He and his followers purchased land from the Narragansett Tribe and founded Providence, Rhode Island in 1636 with an elected government “in civil matters only,” and received a Charter for Rhode Island in 1643.

In 1638 Williams would start the first Baptist church in North America, becoming a powerful force in the concept of the “wall of separation” between the state and religious bodies, and the right to freely worship. (Thomas Jefferson would later use his phrase in a famous letter to the Danbury Baptist Association.) Both Jefferson and James Madison gave credit to Williams as the inspiration for the First Amendment.

Also In 1636, the Rev. Thomas Hooker and other ministers founded Connecticut with an elected government, and Hooker penned the first written constitution in the

Colonies. It would formalize the written documents used in other colonies that shared the Biblical perspective of liberty expressed through elected legislatures, defined the powers of the government, and established the first protections of individual civil rights and freedoms.

Crown-appointed Governors in New Hampshire, Virginia and Georgia who ignored or attempted to disband these elected bodies were met with minister-led opposition, and fiery sermons on the civil rights of sovereign citizens. When there was an attempt to abolish the elected bodies in Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts and force the Anglican Church on those colonies, ministers and pastors were in the forefront of opposition. In 1687, the Rev. John Wise of Ipswich, Massachusetts was jailed for leading a protest against taxes imposed without the approval of the legislative body, by the crown-appointed Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Wise was also the author of critically important essays that spread his stature as a leader throughout the colonies, as he powerfully asserted that liberty and the right to elect representative government was God’s plan in both the church and the state, and were core Biblical principles. It was Wise who first wrote that “taxation without representation is tyranny” and that “the consent of the governed is the only legitimate basis for government.”

So profound and deep was the shaping of the ideas that would later be found in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, that historians could track many of those ideas directly to the writings and sermons of the early American clergy, especially John Wise. Whole phrases and sentences ended up in the Declaration of Independence virtually word for word.

Historian Alice Baldwin would portray the Constitutional Convention and the written Constitution as, “children of the pulpit.”

While the early colonial ministers helped lay the intellectual groundwork for the future nation (along with the Enlightenment thinkers of the century), the Great Awakening – an empowering evangelical revival that swept the colonies in the 1730’s and the 1740’s – helped establish the character of the coming revolution.

Beginning with the powerful preaching of the Rev. Jonathan Edwards who held the first revivals in the early 1730’s at his Northampton, Massachusetts church, the Great Awakening emphasized personal salvation by God’s Grace alone, the authority of Scripture and personal responsibility for moral living. Edwards’ preaching intersected perfectly with the growing democratic spirit in the colonies, and diminished the influence of ritual and established worship, while elevating the role of personal faith, prayer and moral accountability.

The spiritual revival that Edwards ignited became one of the most determining events in American history.

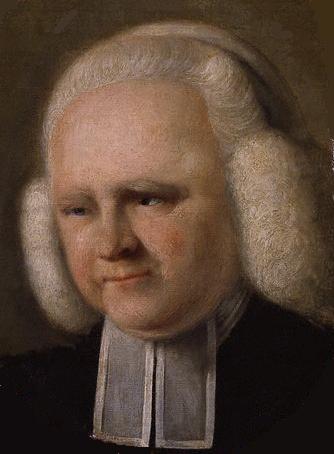

Rev. George Whitefield

His last sermon during this trip through the Colonies was given at Boston Commons before 23,000 people, at a time when Boston’s population was only 15,000. (Whitefield and Benjamin Franklin became good friends; while listening to Whitefield preach in Philadelphia, Franklin paced off the distance until he could no longer understand Whitefield and, ever the scientist, estimated that at two people per square foot, Whitefield could be heard in a crowd of 30,000!)

The importance of the religious leaders in both educating the public and providing intellectual support for the cause of Liberty, and then actually fighting during the Revolutionary War was not lost on the British, who called the pastors, ministers and their congregants supporting Independence, the “Black Robe Regiment.” The essential place of pastors and ministers in the Revolution was so obvious that John Adams exclaimed, “The pulpits have thundered.”

There were many in England who considered the war as the outcome of the nearly two century old theological battle between the Presbyterians and Congregationalists, and the Church of England. But even that division did not capture the power of the emerging concept in the Colonies that resisting tyranny was both Biblical and moral. When the war came, this idea had even split the Church of England in the Colonies, where up to half the clergy, who had sworn an oath to the Crown upon ordination, left their pulpits, and some Anglican congregations re-wrote their Book of Common Prayer to remove its prayers for the King as head of the church. Many of the loyalist Anglican priests returned to England.

With this amazing inheritance you would think that America’s current religious leaders would be in the frontlines of the new battle in the 21st century for human liberty and the freedom of religion, speech and association. Instead, with a few exceptions, religious leaders and religious organizations are irrelevant bystanders in the new America, or all too often cheerleaders for the devolving culture and the radical left.

The minimal pushback from conservative and orthodox religious leaders to the incorporation of socialist and authoritarian constructs throughout the society, the education establishment, the attack on the First and Second Amendments, and ignoring the profound issues of government created poverty , hunger and class warfare, is hard to understand. Equally puzzling are the abandonment of essential doctrines explicit in Scripture, and the new fad of kowtowing to the lowest common denominator in our culture in the areas of sexuality, marriage and moral responsibility.

Where are the bold and visionary religious leaders today who are informing, educating and shaping the worldviews of future generations of citizens? Where is the public preaching on the powerful connection between Biblical truth, the inalienable rights of men, and a just and limited government? Where are the leaders that denounce radical progressivism and tyrannical governments as foundationally evil, because by design they employ pride, envy, and set one person against another? Or they use covetousness to pit one group against another, and inevitably crush individual freedom?

It is ironic, that these free men and woman have so much to lose when the day comes where they have no pulpit from which to thunder. Perhaps the only answer is that, like our colonial predecessors, we must have a revival of the mind and a revival of the spirit – not only in our leaders, but in ourselves first. Then we can pull the leaders behind us.

Could it be that the new struggle for liberty in the 21st century won’t be won in Washington or in the pulpits, but in our own hearts as we respond to the same God that emboldened a group of ragtag Colonies to resist the most powerful nation on earth, and to set the American story in motion?