Over the 60+ years of our marriage my wife and I have driven hundreds of thousand miles in cars old and new. The cars we drove have spanned almost a century in model-years.

I have loved cars and the American road since the 1950s. My Pop repaired cars professionally, so my brothers and I saw all kinds of cars in various stages of repair. We gained some understanding of how cars work, got hands-on experience repairing them, and drove vehicles of every age and description. Sometimes we saw cars that had been in terrible wrecks. My brothers became accomplished mechanics, and even I gained some skills and knowledge. Each of us was college educated and had technical careers, but we still love cars, both old and new.

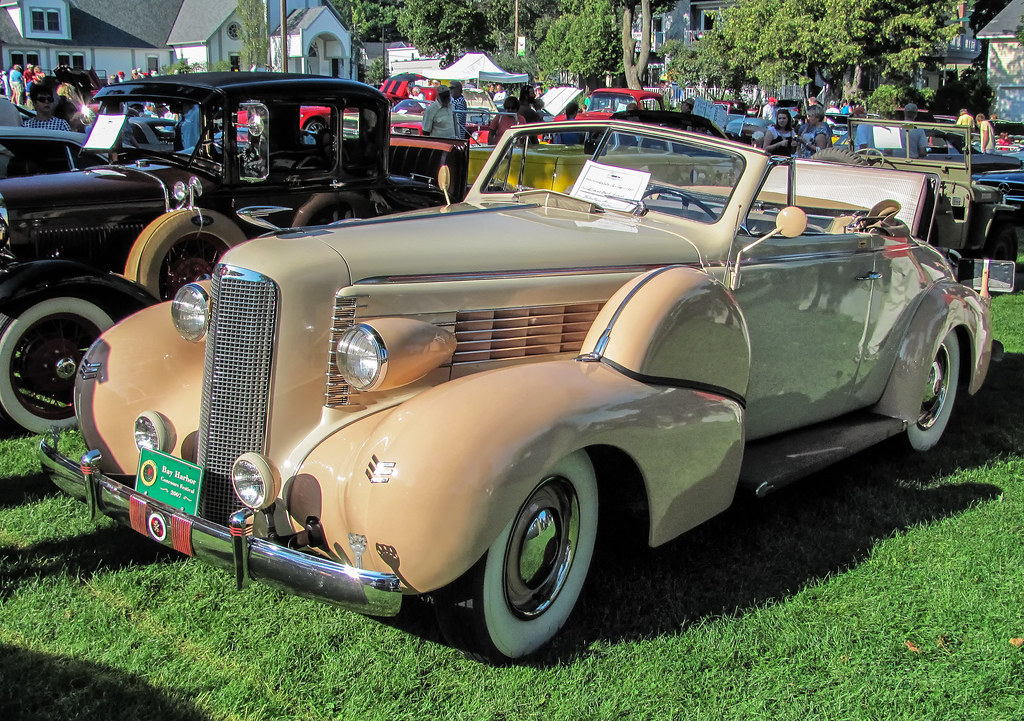

A favorite early memory for me was the 1937 La Salle roadster driven by Pop’s mechanic, Tommy. You’d have to look far and wide to find a more beautiful, stylish car. (La Salle was a division of Cadillac motor cars. Their models were produced from 1927 to 1940.)

My love affair with cars predated driving age. I was ten when my father brought home a gigantic limo-class Buick – a 1941 Limited model – that seemed a city block long. He bought it slightly damaged from a doctor who had a fender-bender while passing through town. The car looked as though the rear seat had rarely been used. It easily accommodated our family of five kids.

We had grand times with that car. It was a kind of sleek pre-van (before the van was actually invented). The guys from the Boy Scout troop called it “The Hearse.” The massive car’s body-joints were all sealed with lead, and the huge straight-8 engine featured serially linked dual carburetors. For economy, the first carb handled ordinary driving. At high speeds, or when the accelerator was punched, the second one kicked in for extra power. It was impressive to feel the huge car leap forward from a speed of 65 mph when that second carburetor engaged.

The Buick seemed indestructible, but one day in 1955 my mother crumpled a front fender when she struck another car whose driver had run through a stop sign. The accident was actually a financial boon because Pop and his long-time friend and colleague Frank had just started their own business. The car my mother hit became their first repair job. (She got a lot of kidding about generating business for the new shop.)

But the Buick was crunched. Pop was far too busy to spend valuable time on it. He bought a replacement car and parked the banged-up Buick on the shop’s back lot.

We kids wouldn’t let it go, however. We pleaded for the Buick’s repair, and being a soft-hearted guy, Pop called junkyards all over Pennsylvania to find a fender – already rare in 1955. One cold December evening we drove to a parts-yard 60 miles away to retrieve the massive part. (It must have weighed 100 pounds.) The Buick was restored to operating condition and launched into an extended lifetime with several members of the family – far outliving Pop, who died in 1969.

People were always phoning Pop, trying to sell him cars. One day, just after I had finished high school, I was at the shop pulling radiators out of cars for repair. (Radiator repair was Pop’s specialty.) He beckoned and said, “Come on, we’re going into town to look at a car.”

At the designated address we found a family of grown children gathered glumly round the kitchen table, as families do when someone has died. But there hadn’t been a death. They were just grieving because their beloved family car, since 1938, was going. (I could identify.) It was a ’38 Plymouth – 22 years old and a little worn, but still drivable. (Humphrey Bogart drove a ’38 Plymouth Coupe in the film High Sierra.)

We paid $20 for the Plymouth. You sat up high in the cab. The yard-long shifter was mounted in the floor next to the driver. I was licensed, but not yet practiced in stick-shift, so Pop showed me the H-pattern and how to operate the clutch. I lurched away into traffic and drove home.

I drove that old Plymouth all over New York State during my second year of college. One day it was so cold (-10o F) that the antifreeze turned to slush and the engine overheated. I left the car on the shoulder of a back road and returned a week later with a classmate to get it running again. The old flivver used oil copiously, so I carried a large can of it in the trunk.

When I got married, I gave the Plymouth to my brother Al. He disbelieved the oil gauge and promptly ran the engine dry of oil. The bearings burned up and the pistons seized in a cloud of smoke. Al then found a ’37 Dodge which he drove until he banged up the front end one rainy day. My forlorn old ’38 with the burned-up engine gave up its fenders, grill and hood to fix Al’s car.

By then an accomplished mechanic, Al dropped a modern Pontiac V-8 into his early hybrid and drove it (at alarming speeds) back and forth to college in the late ‘60s. Finally, short of funds, he sold his rod to a classmate. Only memories remained of the ’37-’38 Plymouth-Dodge. Later, Al resurrected the ’41 Buick and drove it all over the country in 1970. (Gas was 25 cents a gallon.)

Pop gave us a ’53 Cadillac as a wedding present in 1962. We drove it for several years before trading up to newer models. Over the years I acquired a ’38 Buick, ’41 Cadillac and ’56 Chevy – fun hobby-cars, but a lot of work to maintain.

Driving has changed since 1960, when we bought the old Plymouth. My 1959 driving instructor drilled me on parallel parking and the three-point turn, as the license-test specifically addressed both maneuvers. I practiced them for hours. Today, suburban drivers rarely use either technique. I doubt if they are even tested any longer in Northern Virginia, where we live.

The three-pointer lets you reverse direction in a narrow space with three tight turns – forward, reverse, and forward again – without bumping the curb. The maneuver requires the driver to have complete control of the car and an accurate sense of its size. How the turn is executed tells the examiner a lot about the driver’s level of skill and comfort with the vehicle.

Another part of driving that has changed – not necessarily for the better – is highway passing. The multi-lane superhighway was rare in the ‘50s, so passing-technique was taught with the two-lane road in mind. We learned to accelerate and pass quickly on such roads – never lingering next to the other vehicle or meandering by at the speed limit. The danger of driving in the opposing lane made speed limits a secondary concern. You passed and returned to your proper lane quickly.

Today, the multi-lane highway has eroded the technique of passing in several respects. First, the concept of the “passing lane” is all but lost. The left-most lane on a multi-lane highway is supposedly reserved for passing. But “boulevard driving” has conditioned drivers to occupy any lane at any time, at whatever speed they choose, without any concern for drivers wishing to pass. The “passing-lane cruiser,” driving at the speed limit (or less), followed by a line of would-be passers, is a common sight on the modern superhighway. In my experience, that passing-lane driver is sometimes a policeman.

The second major erosion of passing derives from the emphasis on low-speed driving during the 1970s energy-crisis era. Starting in the mid-1970s, and well into the ‘80s, highway speed was federally limited to 55 mph – even on roads built for much higher speeds. This restriction is no longer in effect, but many motorists retain that era’s misconception that the speed limit cannot be exceeded under any circumstances. My era’s teaching that you pass as quickly as possible has morphed into a slavish concern for the speed limit, to the neglect of all other considerations.

This has produced the dangerous practice of low-speed-differential passing – e.g., a car traveling 65 mph passing a car or truck traveling 64 mph. The 1 mph. differential equals 1.5 feet/second. At that differential speed it takes 46 seconds to pass a 70-foot-long truck. By focusing on the speed limit, the passing driver ignores the risk of driving alongside a big truck for all that time. One twitch from one of those monsters will send him off the road and into oblivion.

The long line of cars and trucks following the slow passer is also very dangerous. Often I see (or am part of) a clump of dozens of vehicles – all following much too closely in a pack for ten, fifteen, or even twenty minutes – trailing a speed-limit passer on his maddening, cruise-controlled way. Wild maneuvers by frustrated drivers trying to get past him magnify the risk.

Trucks often do low-speed-differential passing, too. This is particularly trying when one truck passes another on an upgrade – both driving well under the speed limit. Some states deny the left lane to trucks, but this is rare. I am sensitive to the danger posed by trucks and try to stay away from them.

I always minimize the time I spend next to another vehicle. To pass, I increase my speed by 10 mph or more, resuming my regular speed after passing. If I overtake a slow-passer, I usually flick my lights once to let him know I’m there. Usually, he completes his pass quickly and lets me go by, but not always. Sometimes I have to wait until he crawls past the other vehicles.

The durability of cars has also changed since I started driving. Today you can still see a ’64 or ’65 Mustang or ‘60s muscle-car on the road. That’s nearly a 60-year-old car! In the ‘60s you didn’t see many cars that age. Worn-out 1910s or 1920s cars had been turned into scrap years earlier.

Engine durability is much improved because of advances in metallurgy and design. Valves don’t burn the way they used to. Cooling systems are better. Rings and pistons are far more durable. I drove a 1985 Toyota Celica 216,000 miles, taking care to change the oil regularly. The power train was never touched. It still ran perfectly and had the original cloth top when I sold it in 2000. In the 1950s you could expect major engine repairs by 100,000 miles.

Another improvement has been enhancement of driver-safety by changes in how cars are structured. From the 1920s thru ‘70s cars had a rigid chassis and frame that tended to transfer the force of a collision into the passenger-compartment. This helped the car to withstand an accident, but it was dangerous for the passengers, who got knocked around like ping-pong balls and were often thrown out of the car. Today the rigid chassis is gone, so the car’s body crumples up in an accident – absorbing most of the energy of the collision, but sparing the passengers. People can often walk away from an accident unharmed, but their crumpled car is junk.

We truly live in a blessed time from the standpoint of car reliability, power, safety and economy. I often think of how Pop would marvel at today’s cars. Our V-6 Avalon sedan sips gas to give us 30 miles per gallon, but furnishes any speed we need. It’s a long way from the ’38 Plymouth with the 5-gallon can of oil in the trunk. Still, those were the days…