Although I rarely visit our local post office – actually, I make every effort to avoid it – I stopped in recently when the need to mail a package left me no alternative. I stood on line for nearly 30 minutes as two clerks slowly stamped, snipped, wrote and pasted their way through the 15 customers initially ahead of me. Occasionally each clerk disappeared for long periods of time into the rear area of the office. One customer in the queue actually collapsed – probably of hunger. No one carried him out. We had to step over him. (OK – it could have happened…)

Two of the four service-windows were empty. Of course, this was partly my own fault. I had carelessly arrived during the lunch hour, when many business people try to do their postal business. But there are always fewer clerks present then. (After all, they have to eat, too.)

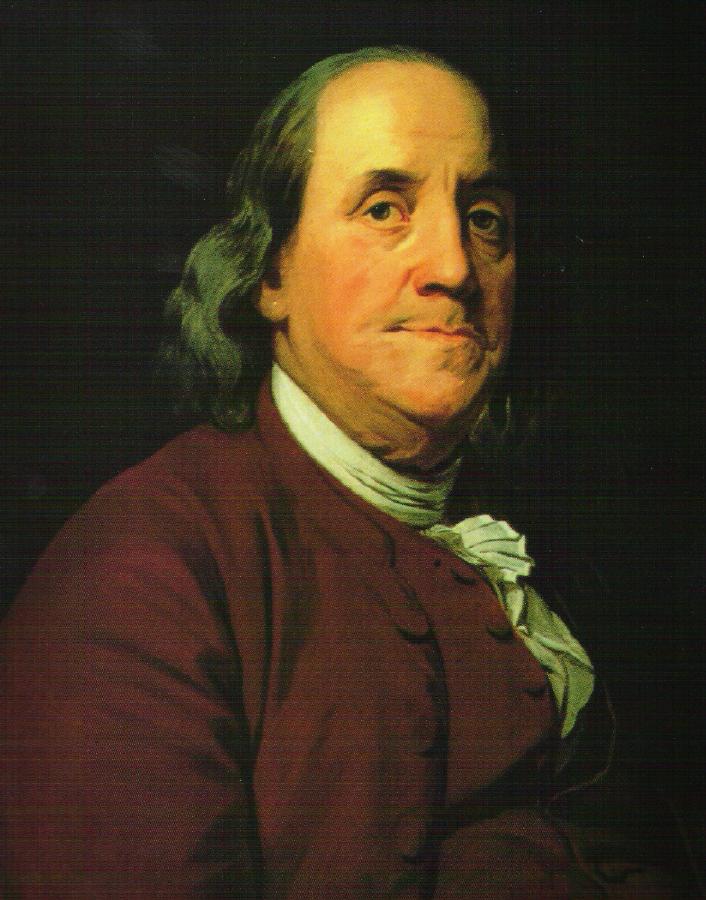

As I counted the ceiling tiles, and eventually the floor tiles, I mused on the fact that Benjamin Franklin, the founder of the United States Postal Service, would probably feel right at home if he could visit any local post office today. A “modern” post office (an oxymoron as ever was) is a Blast from the Past. No business concern today has so faithfully retained the tools, methods, look and feel of the 18th century. Apart from the electric lighting, stepping inside one is like going back in time.

To begin with, there is the Post Office’s signature: a long, slow-moving queue of customers. In most modern business establishments, managers frantically scour the store’s back rooms for extra staff if a queue of more than three or four customers builds at the sales counter. Managers have even been known to try to hire passers-by in the street when they are short of salesmen or cashiers. Nothing must be allowed to retard the ka-ching of the cash register. Heaven help any staffer whose slowness causes customers to leave the store without buying. A California jury acquitted a store manager who lashed a cashier through the mall after three customers left his queue while he fiddled with a malfunctioning cash register. (Oops, there I go again…)

Of course, there are exceptions to this modern “rule of queues.” Certain restaurants seem to prefer long lines of customers – perhaps to demonstrate the establishment’s popularity. Medical offices do this, too – possibly to emphasize the doctor’s importance. Stores like Home Depot also seem chronically short of staff. (One wag speculated that most HD-staff must be either illegal aliens or people in the Federal Witness Protection Program – none of which would want to risk being seen.)

Thus, the post office – if not exactly unique – is part of a very select company of establishments that don’t mind making their customers cool their heels for long periods whilst awaiting the service offered there. One imagines that long, tortoise-like lines were common in earlier centuries when few people wore wrist-watches and even fewer had vanloads of kids waiting to be taken to soccer practices or music lessons. We once visited 18th-century Fort Louisbourg in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Its clock had only an hour hand. The guide told us that Frenchmen of that era thought there was no need to measure time more finely than by the hour.

18th-century “technology,” however, is the Post Office’s particular hallmark. Where else do clerks actually mark documents and other materials with inked rubber stamps, painstakingly paste labels onto envelopes, make customers fill out detailed documents by hand, stroll back and forth to drop items in bins far from their work-station, and vanish for long periods?

At the grocery store I hand the cashier a small encoded card which hangs from my car-keys. Instantly he knows, via the store’s central computer, who I am and how much I have ever spent in that store-chain. At the airline check-in counter a constantly moving conveyor belt takes luggage to a sorting point. Tickets and boarding passes are produced electronically. And in some restaurants the cashier enters your order into a computer which conveys it to the food-preparers. Nothing is written down or conveyed orally. Your sales-receipt contains your order number.

All modern businesses use register-scanners to check out customers’ purchases. If addresses or other data are needed, clerks quickly key them in. Rarely do customers fill out forms in longhand, except at medical offices – another throwback to the past.

Nearly all activities in a post office could be automated into a comprehensive computerized system in which pen and paper would seldom be touched except to sign the credit-card voucher – and probably not even then. (Even Home Depot has virtual pads for your signature.) You would hand the high-tech clerk your plastic postal card, which would bring up your name and address. Destination address-data would be quickly entered by the clerk from a note the customer prepared before arriving. The type of delivery would be clicked; the correct delivery label would be printed and applied. The package weight, the origin and destination zip codes, and the delivery type would be linked to calculate the cost in a wink. An overnight or special delivery parcel could be prepared in a few seconds instead of the several minutes it now takes a clerk.

In the truly modern post office, clerks would still sell standard or special-issue stamps, but a customer desiring only stamps wouldn’t wait in line. Banks of vending machines would dispense all denominations of postage, just as ATM-machines dispense currency. The machines would take any currency denomination, as well as credit cards. This would drastically cut the length of post office queues everywhere.

This dazzling vision of non-purgatorial trips to the post office for millions of people, however, is unlikely to materialize for a single reason: the USPS doesn’t have to do this. They are fine the way they are because they have what no other business has – a government sanctioned monopoly. Except for package-delivery businesses like Federal Express, which the USPS sanctioned, nobody else can go into the business of delivering the mail. However slow or inefficient the postal service might be, the government guarantees them a profit. It’s a beautiful arrangement.

Because the USPS lacks competition, it doesn’t need to restrain its labor costs. Executives receive huge salaries, and every year lavish bonuses are spread across middle-management ranks. USPS workers are organized under a powerful union which has pushed pay and benefits for its workers into the stratosphere. If you can get a job with the post office, you’re set for life. Those high salaries and the lack of modernization help explain why a first-class stamp today costs 16 times what it did in the late 1950s – far beyond the overall rate of inflation.

A high-tech post office, along the lines described above, would require clerks to be computer-literate technicians deserving of their high pay-levels. Efficiency would go up. USPS labor costs would actually decrease because fewer clerks would be needed. Technology would replace unskilled labor. Postal rates would stabilize or even diminish.

All this further indicates why change is impossible under the current system. The USPS union would fight to the bloody last to prevent replacement of its legions of well paid workers with fewer, highly skilled workers. The status quo is a deal they won’t give up easily.

If the electronics industry had resisted modernization the way the post office has, televisions would still be black-and-white and would cost $10,000. Personal computers wouldn’t exist because makers of large main-frames would have blocked their development. As for cars: we would still be driving hand-cranked Model Ts costing $50,000.

The current financial deal with the USPS is a legacy of LBJ’s Great Society. Democrats engineered it while they controlled Congress, so they’ll hold onto it with a death-grip reminiscent of Social Security. This leaves the task of modernizing the postal service mostly to Republicans. If they can learn to wield power as Democrats did, maybe they’ll get round to doing something about Ben Franklin’s antique. Meanwhile, bring a book or some knitting when you visit the post office. You’ll have a long wait.