War has been a significant electoral factor in American presidential elections for close to two centuries, as we can see from earlier history, which I’ll summarize here:

1860. Southern states had warned that they would secede if Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected. When Mr. Lincoln won because two Democrat candidates – Stephen Douglas and John Breckinridge – split the pro-Democrat vote, eleven Southern states formally seceded from the Union and formed the Confederacy. Soon after that, in Apri 1861, Confederates used heavy guns in Charleston harbor to bombard Fort Sumter for 36 hours, forcing Union troops to surrender the fort. These were the opening shots in a Civil War that lasted four years and cost over 600,000 dead.

1864. With the Civil War dragging on in its fourth year, and casualties mounting to unheard-of levels, Union voters were heartily sick of the war. Fully aware of this, President Lincoln expected to lose the November election to Democrat George McClellan, previous General of the Army of the Potomac. Electoral prospects looked bleak for Mr. Lincoln through most of 1864, until General Sherman’s “march to the sea” and capture of Atlanta. Those successes persuaded voters to support Lincoln’s plan to defeat the Confederate armies, win the war, and restore the Union. Mr. Lincoln won a second term, but Confederate activist (and actor) John Wilkes Booth assassinated him in April 1865, just a week after Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses Grant.

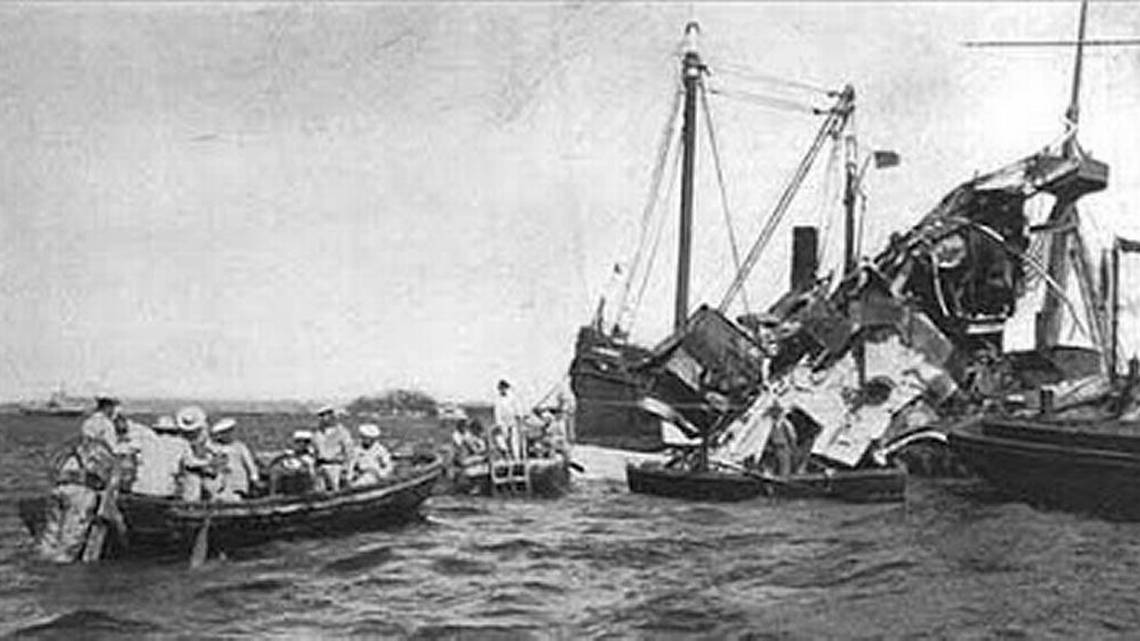

1898. “Spain, Spain, you oughtta be ashamed, for blowing up our Maine,” was the verse from her teen-years that my grandma often recited. It commemorated the explosion of our Battleship Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898. Our government (and many American voters) blamed Spanish operatives for destroying the Maine, although later investigations indicated that an internal fire in the ship’s coal-bunker might have caused the explosion. Nevertheless, a war-hungry public enthusiastically went to war on Spain in both the Philippines and Cuba.

“Oh dewy was the morning, upon the first of May,

And Dewey was the Admiral, down in Manila Bay.

All Dewy were Regent’s eyes, them orbs of royal blue.

And Dewey feel discouraged? I Dew not think we Dew!”

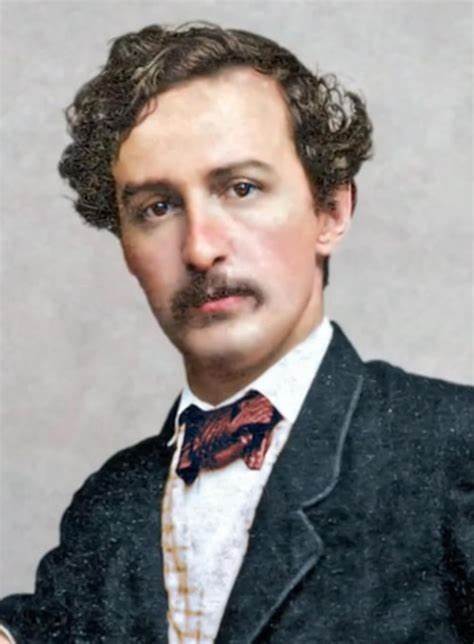

Thus ran some doggerel written by Eugene Fitch Ware to celebrate Admiral George Dewey’s power-altering defeat of the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay on May 1, 1898. Theodore Roosevelt’s famous Charge up San Juan Hill, in Cuba, also happened in the same year. Historians called the tidy little war against Spain an extension of our so-called Manifest Destiny.1 It clearly helped to re-elect President McKinley, with Teddy Roosevelt as his vice-president. Less than a year later Mr. Roosevelt became president when Mr. McKinley was shot by an assassin whose gun was hidden in a bandage on his hand. Mr. Roosevelt was the first war-leader to become president since U. S. Grant. Mr. McKinley was the last U. S. president who served as a soldier in the Civil War.

1916. With Europe locked in a catastrophic war for two years, President Woodrow Wilson campaigned on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Voters gave him a second term on the strength of that implicit peace-promise. But then came the infamous Zimmermann Telegram – publicized by British agents who had decoded it. The Telegram revealed Germany’s promise to help Mexico recover Texas, Arizona and New Mexico, should Mexico enter the war against us. The telegram’s details, plus Germany’s resumption of “unrestricted submarine warfare,” so enraged the American public that Mr. Wilson was compelled to ask Congress to declare war against Germany and the Central Powers. He did so in April 1917, just a month after his second term began. Entry into the Great War was our first-ever involvement in a war on European soil. It made us a world power and Mr. Wilson a world statesman. But the president broke his health conducting a whistle-stop campaign across the USA to gain public approval for the 1919 Versailles Treaty. Thereafter, for the last seventeen months of his presidency, his wife, Edith, acted as his unofficial substitute. Mr. Wilson never obtained Congressional approval for the Treaty. He was the last president with a boyhood memory of the Confederacy.

1940. President Roosevelt broke tradition by running for a third term in November, as Europe was locked in another World-war. The British people were suffering terribly during the Blitz, and Mr. Roosevelt wanted to help them in their struggle against the Nazis. But he knew the public would not approve our entry into the hostilities. So he offered what aid he could with Lend-lease and other initiatives, stopping short of an outright declaration. Approving Mr. Roosevelt’s restraint, voters gave him an unprecedented third term. A year later, the Japanese surprise attack on our naval base at Pearl Harbor enabled Mr. Roosevelt to obtain a declaration of war against Japan, but he didn’t attempt to join Britain’s war against the German Reich. Only after Hitler unexpectedly declared war on us – apparently because of our declaration on Japan – was Mr. Roosevelt able to obtain a war-declaration against Nazi Germany.

1944. Our armed forces’ successful D-Day invasion, breakout from Normandy, and race across France and Belgium persuaded the American public that our war-effort was going well. President Roosevelt’s apologists argued that we shouldn’t “change horses in midstream.” Even Mr. Roosevelt’s Republican opponents seemed to agree, as their candidate in the 1944 election ran a tepid campaign that didn’t mention the war. Mr. Roosevelt easily won a historic fourth term, but it was obvious that his visibly failing health would probably not let him complete it. FDR collapsed and died in his Warm Springs, Georgia, vacation-home on April 12, 1945, three months into his fourth term. He had served as president for 12 years, 1 month, and 8 days. Millions of Americans could remember no other president.

1948. After FDR’s death, Vice-president Harry Truman took over. He oversaw the conclusion of our war in Europe, approved the atomic bombing of Japan, and presided over the conclusion of the Pacific War. In 1948 the Berlin Airlift occurred, and Israel was created as a Jewish homeland by the United Nations. The public approval of FDR’s handling of our war effort was transferred, at least in part, to Mr. Truman. In November he narrowly defeated favored Republican candidate Thomas Dewey after the Chicago Tribune prematurely reported his defeat. Mr. Truman had earned a presidential term of his own.

1950. During Mr. Truman’s second term the 22nd Constitutional Amendment – limiting presidential service to two full terms, plus no more than two years of an assumed term – was ratified by 36 of the 48 states. After North Korean armed forces crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea in June 1950, the UN Security Council voted to oppose North Korea’s invasion with military force. Following that UN vote, with no declaration of war to authorize what he insisted on calling a “police action,” Mr. Truman sent armed forces to Korea – ultimately totaling some 1.8 million soldiers, sailors, air force pilots, and marines. Over 36,000 of these were killed, and some 103,000 wounded. In November Mr. Truman narrowly escaped an assassination attempt by two Puerto Rican nationalists at Blair House in DC.

1951. Our forces in Korea, commanded by WWII General Douglas MacArthur, saw some initial successes, including brilliantly executed amphibious landings in the rear of North Korean forces at Inchon. US armies were driving into North Korea when the Chinese Communists suddenly sent 300,000 fresh troops into the war. In the bitter cold of November 1950, units of our 8th Army retreated to safety from a trapped position at Chosin Reservoir. Thereafter, the war degenerated into a stalemate that produced casualties, but no progress. General MacArthur wanted to invade Chinese territory, wage total war, and possibly use atomic weapons to win. But Mr. Truman feared that expanding the war in this way might pit us against the USSR in an Asian land-war. After the general made public statements disagreeing with the Truman war-plan, Mr. Truman relieved him of command and recalled him to the Continental USA. MacArthur’s firing, revealing the no-win war strategy as it did, reminded war-weary Americans that they had essentially been “at war” for 10 years, and had had 20 years of Democrat-rule. People were hungry for new leadership, which they saw in General Dwight Eisenhower – popularly known as Ike.

1952. Although Mr. Truman was exempted from the 22nd Amendment’s two-term limit, he declined to try for re-election in 1952. He could see which way the political winds were blowing; he was 68; and he had had enough. After leaving office he refused all high-paying business offers, saying the presidency was “not for sale – not by me, anyway.” (Yes, a president actually said that in those “good old days.”) Out of office, Mr. Truman had no financial resources except his World War I pension. In 1958 the Congress passed the Presidential Pension Act to give Mr. Truman and future ex-presidents a comfortable retirement. (Former President Herbert Hoover was also still living.) President Eisenhower oversaw the end of the Korean war in mid-1953 when North Korea signed an armistice. Some historians claim that Ike threatened to use the atomic bomb if they didn’t sign.

1960. Vice-president Richard Nixon ran against rich war-hero John Kennedy in 1960. Nixon stood on Ike’s two terms of peaceful governance, but he didn’t look attractive on TV with his permanent 5 o’clock shadow and ominously low voice. His opponent was a handsome senator who looked (and acted) like the college playboy that girls swoon over. Mr. Kennedy’s claim of a negative “missile gap” between us and Russia was the closest thing to a war-factor that could be found in Ike’s peaceful nifty-fifties. The claim was never verified, but a recession caused by a 4-month Steelworkers strike (July to November 1959) also let JFK and his party say, “We can do bettah.” On Election Day, the vote was dead-even until Chicago Mayor Daley gave Kennedy a late-night win with his classic “late-reporting precincts.” In fact, there was so much evidence of election-cheating in Illinois and West Virginia that President Eisenhower urged Mr. Nixon to call for recounts. But Mr. Nixon refused, saying that it would be “bad for the country.” Two years later, we found ourselves a whisker away from war with the Soviets, who had installed nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba. Historians believe that Kennedy’s chance meeting with USSR Chairman Nikita Khrushchev in 1961 had convinced the Stalingrad tough guy that the president was just a clueless frat-boy who could be pushed around. Ultimately Mr. Kennedy became the victim of an underground war in his own country when he was assassinated on a Dallas street in November 1963.

1964. A year after JFK’s death made him president, Lyndon Johnson ran for a term of his own. Polls showed that he was a shoo-in, due to the JFK sympathy-vote, but the second Accidental President Johnson2 wanted an extra boost. He got it when North Vietnamese gunboats reportedly fired upon our naval vessels in the Gulf of Tonkin on August 2, 1964. This allowed LBJ to act (as one reporter put it) “all Commander-in-chiefy” just before the election. Historians have argued, ever since, over whether the Tonkin event really occurred, and how those reports affected the ‘64 election. Mr. Johnson won 61% of the popular vote – becoming the only Democrat to win a popular vote majority, 1944-1976. With all that public support behind him, LBJ evidently felt empowered to get us into a real shooting war in Vietnam. In March 1965 my colleagues and I were listening by radio as LBJ called for 500,000 troops to set things right in “Veet-nam.” One of our group remarked on how lucky we were. “If we had elected Senator Goldwater,” he said, “we’d be in an Asian land war for sure.” It was classic “gallows humor,” but the public – particularly draft-age males – didn’t feel very lucky or jovial about fighting some little dudes in the Asian jungle who had done us no harm. LBJ tried to calm the public by promising both “guns and butter’ – meaning no rationing – but he failed to mention that this would involve a go-slow, no-win war. When this became evident, an anti-war movement quickly arose to bedevil LBJ for his entire term. This was also our first time fighting a war in which our news media were not our full allies. That media-model, established in Vietnam, continues to the present day.

1968. The Tet3 offensive, which surprised the American public and news media on January 30th, was a military disaster for North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces, but a roaring public relations success for them. When Walter Cronkite – the senior reporter trusted above all others by the American public – declared that the war was “lost,” it was the kiss of death for LBJ’s limited war strategy being managed by Robert McNamara and his academic Whiz Kids. The Tet attack discouraged the public and strengthened the anti-war movement, which had found a champion in LBJ’s own party – Robert Kennedy, brother of JFK. So capable did Senator Kennedy look, and so strong did the anti-war movement appear, that LBJ announced in March that he would not run for another term as president. Senator Kennedy looked like a sure thing for the Democrat nomination, but it was not to be. His assassination in June – soon after Martin Luther King’s was killed in April – roiled the political waters, but the War’s bloody non-progress still looked like the decisive factor for the election. Both Richard Nixon and Senator Hubert Humphrey ran on promises to end hostilities. Mr. Nixon won – primarily because of public-dissatisfaction with the war – but Alabama Governor George Wallace was a surprise third party-factor who carried 46 electoral votes of five southern states which normally would have leaned Democrat. The governor’s platform was racial segregation. Earlier he had blocked school-integration in his state by standing in the schoolhouse door and proclaiming, “Segregation now, segregation forever!” He was the first third-party candidate to win electoral votes since 1908. Finishing the Vietnam War became President Nixon’s main task. It took him four years to do it, but by that time it had become Nixon’s War. That LBJ had started it was conveniently forgotten. Eight-year wars are far beyond the public’s tolerance.

2004. We were at war again in 2004 because of the shocking terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Democrat presidents had taken us into all four of our 20th century wars. But George W. Bush was a Republican president, so Democrats seized upon his war against Iraq as a political club which they used to bash him. War became a major factor in the election. Mr. Bush won a second term, but war-weariness gave Democrats control of both houses of Congress in 2006.

2008. The newly peaceable Democrats ran attractive, well turned-out Senator Barack Obama as the antidote for George W’s “warmongering.” Mr. Bush’s leadership in the aftermath of the 9-11 attacks was forgotten; in fact, it was denounced by some Democrat-partisans. And their impeccably dressed peace-candidate – who promised to “fundamentally transform America” – soon showed himself to be an out-and-out socialist who intended to do just that. Mr. Obama declared that he was elected to end wars, not start them. Evidently, he meant foreign wars, because his two terms featured war on the cops, war on fossil fuels, and war on racial harmony. He was all war, all the time.

2016. After eight years of Obama-style “peace,” voters were ready to pass the baton to someone who looked like he might actually do something useful. They didn’t want Hillary Clinton, even though she had declared that it was her turn. Instead, they elected a tough, coarse-talking New York billionaire who gave as good as he got and called things by their true Anglo-Saxon names. Denizens of the Establishment Swamp knew he posed a threat to their bipartisan political arrangements, so they threw everything they could at him, including the kitchen sink. First, they tried to keep him from winning the election. When that didn’t work, they publicized a fabricated Russian Dossier and had a Special Prosecutor disrupt his administration for two years. True to his promises, Mr. Trump turned Washington upside-down, closed the border, made us energy independent, and put more Americans to work than ever before. As a reward for all this, Democrats impeached him twice during his term for “colluding” with the Russians. There was no substance to the charge.

2020. Aided by a mysterious virus that probably came from a lab in China, Democrat governors and mayors crippled the Trump economy, closed schools and churches, and forced millions of citizens to take untested “vaccine” shots that weren’t really vaccines. Death-counts were inflated, people sat at home collecting government checks, and many workers lost their jobs for refusing the poorly tested injections. With Mr. Trump’s once-roaring economy on the ropes, Democrats ran a superannuated, basement-bound Joe Biden as a mystery candidate who would restore “normalcy” and unify the country. Millions of mail-in ballots of unknown validity put Lunch-bucket Joe over the top after days and nights of post-election-day counting. Once in office, he reversed all of Mr. Trump’s productive executive orders, declared war on fossil fuels, threw the borders wide open, and produced galloping inflation by spending trillions of deficit dollars to buy a constituency for his second term. His Department of Justice treated Mr. Trump as a criminal.

2024. This brings us to the current Election-year. A child could see that the Biden administration – having given us 4 years of runaway inflation, 7 million illegal immigrants, high energy-prices, and weak foreign policy – is in deep doo-doo. Gravy Train riders are happy with Joe’s liberal policies and lavish spending, but millions of citizens hunger for Mr. Trump’s productive governing. As the final months of the 2024 presidential campaign pass by – and the (possible) end of Joe Biden’s regime draws nearer – we catch glimpses of the final card Democrats might be holding in the high-stakes game of the presidency. No surprise – that “card” is War! If all other aspects of Good Old Joe’s presidency seem unable to re-elect him, he and his war-hawk advisors might play that card just before voters cast their ballots. Will a war give Good Old Normal Joe another four years in office? We’ll see. There’s a time to make war, but the present day is certainly not that time. If you’re a praying person, pray that the American people will be divinely empowered to resist the war-lovers’ destructive plans. This is a dangerous time.

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.” (Matthew 5:9)

+++++++++

- Spain ceded the territories of Cuba and the Philippines to us after their defeat in the Spanish-American war of 1898-’99.

- Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s vice-president, became the first Accidental President Johnson when Mr. Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865.

- Tet is the Asian name for the Lunar New Year.

3 comments

As if … as if the Right were not the party of might and fight but instead the party of peace! Ha! That will be the day …

Enjoyed this article. My daughter and I were debating if it’s better to speak softly and carry a big stick or some other posture. After going through 20th and 21st century conflicts and Presidential leadership we decided it is best to have a big stick, clearly explain to those who may harm you that you have a big stick, and let them know the reasoning and consequences for putting that big stick into action. Finally, that big stick better be kept from rot and not used to poke enemies. 3 of our presidents got this right.

Excellent Post!